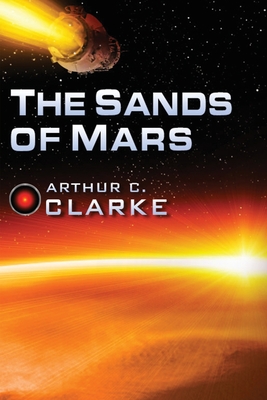

During the years immediately following World War II, science fiction was flowering. It was the genre’s Golden Age. Pulp magazines and newly popular paperback books carried garishly illustrated stories about grand adventures in “atomic-powered” spaceships and encounters with gruesome monsters and vastly intelligent aliens. A young man named Arthur C. Clarke, newly emerging in the field, then came along with a novel that presented a far more sober and scientifically grounded story about a voyage to Mars (up to a point). The Sands of Mars was unusual for its time, and it presaged Clarke’s long and fruitful writing career in hard science fiction. Unfortunately, reading the book now, seven decades after its publication, the story falls flat.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

A passenger on a maiden voyage to Mars

Arthur C. Clarke’s imagined mission to Mars seems to take place sometime early in the twenty-first century. Author Martin Gibson—who, like Clarke himself, writes both science fiction and popular science—is a passenger on the spaceship Ares. The only passenger, actually. And most of the six-man crew is unhappy about that. They regard him as a nuisance, and he proceeds to earn the label in short order.

The Ares is on its maiden voyage to the colony on the red planet. And Gibson is on board to write about the voyage and the growing colony for magazines and newspapers. His romantic tales about Mars had inspired millions, and the company that owns the ship hopes he will help promote travel to Mars. Because the Ares is something entirely new in space. It’s the first spaceship “to be built primarily for passengers and not for freight. When she was fully commissioned, she would carry a crew of thirty and a hundred and fifty passengers in somewhat spartan comfort.”

The Sands of Mars by Arthur Clarke (1951) 295 pages ★★★☆☆

A suspenseful tale

Clarke writes in detail about Gibson’s relatively uneventful three-month voyage to Mars. But the bulk of the story takes place after the ship’s arrival, and the tale turns anything but uneventful. Mysteriously, the Ares is diverted from its planned landing on Phobos, the larger of the two moons, to Deimos, the smaller one—and no one will explain why. Then the ship arrives on-planet carrying a shipment of medicine for “Martian fever,” which threatens to become an epidemic among the planet’s several thousand colonists. While the ship’s doctor administers the drug to the first patients, Gibson meets the intimidating chief executive of the colony and the mayor of its capital, the larger of the two cities, Port Lowell.

As the weeks roll by in Gibson’s planned two-month stay on Mars, mysterious events are unfolding in secrecy. Gibson receives hints of what’s going on, but only hints, and neither the chief executive nor the mayor, nor anyone else for that matter, will answer his questions. Meanwhile, Gibson is involved in a mystery of his own, rooted in his past. There is no shortage of suspense in The Sands of Mars—and the climactic scenes in the book’s closing chapters are full of surprises.

Spoilers here: what Clarke got wrong

In a foreword to the 1966 edition, Clarke describes The Sands of Mars as “one of the first science-fiction novels about Mars to abandon the romantic fantasies of Percival Lowell, Edgar Rice Burroughs, C. S. Lewis, and Ray Bradbury.” And, to give credit where it’s due, The Sands of Mars does reflect scientific reality about space travel as known in the late 1940s when he wrote the book. At least, that’s the case with respect to the voyage to the red planet. Clarke knew his stuff about interplanetary travel. He seems to have gotten some details wrong, but they’re of little consequence. And he wrote two decades before Apollo 11 landed on the moon!

Although Clarke proves prescient about space travel, he is surprisingly unimaginative about more pedestrian matters. For example, he imagines Gibson still writing on a typewriter and using carbon paper more than fifty years in his future. In navigating on the surface, his hero “struggles with a map three sizes too big for the cabin.” And, even though the first digital computers about to enter commercial use, he writes about a “big electronic calculating machine” that appears to be of little value to the crew. To compute a new trajectory for the Ares to land on Deimos, the “astrogator” must devote “several hours of computing.” Disappointing.

But what Martin Gibson finds after he lands on the planet is, in a word, preposterous. Walking on the surface with only a “breathing mask?” Native plants growing on Mars? Plants that mine oxygen from the regolith and provide a source of vital, breathable gas to the colonists? “Martians” that are kangaroo-like animals? “Passenger jets” flying in Mars’s thin atmosphere? And colonists who turn the moon Phobos into a “second sun?” A nuclear furnace so close to the surface that it will warm the atmosphere and begin to terraform the planet? Well, you get the point. All this may have passed for hard science fiction in 1951, but it’s laughable now.

Oh, and one more thing. Gibson and the six men on the Ares crew are all English, as is the leadership of the colony. In Port Lowell, the chief executive enforces a rule that everything must stop in the late afternoon—for tea.

Missions to Mars so far

As of February 2023, Wikipedia lists fifty missions to Mars but classifies just twenty-eight as “successful” and two as “partially successful.” These successes include flybys and orbital missions. (Other sources claim a much smaller number of successes.) NASA has achieved the greatest success, with eighteen fully successful missions and one partially successful. The Soviet Union posted five plus one a partial success in 1971. More recently, three other space agencies have joined the fray: those of China (three successes), the European Space Agency (one), and India (one).

No country has yet attempted to mount a human mission to Mars.

About the author

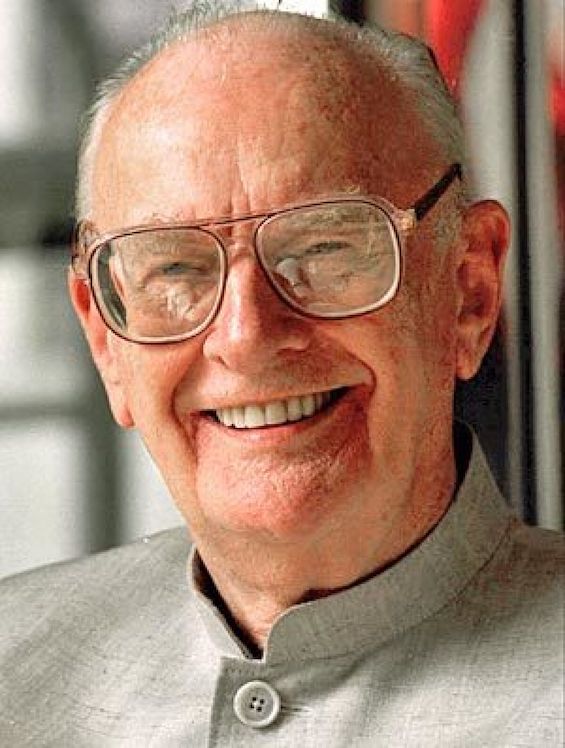

Sir Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) needs no introduction to any serious science fiction reader. His name typically appears along with those of Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein as one of the all-time greats of the genre. Although he is best known for his novel, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and his screenplay for the iconic 1968 film of the same title, he wrote thirty-two other science fiction novels and thirty-four works of nonfiction. However, he is better known to many scientists as the visionary who predicted communications satellites in a 1945 article. Despite the many laurels he received for his knowledge about science, he possessed only a bachelor of science degree (from King’s College in London). Clarke was born in England but lived much of his life in Sri Lanka, where he pursued underwater exploration. He was knighted in 2000, eight years before his death.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed three other books of the author’s:

- Rendezvous With Rama (Arthur C. Clarke’s believable First Contact novel)

- The City and the Stars (Far-future fantasy from Arthur C. Clarke)

- The Collected Stories of Arthur C. Clarke, Audible Edition, narrated by Ralph Lister, Ray Porter, and Jonathan Davis (The SF stories of Arthur C. Clarke aren’t great)

For more good reading, check out:

- These novels won both Hugo and Nebula Awards

- The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels

- 10 top science fiction novels

- The top 10 dystopian novels

- 10 new science fiction authors worth reading now

- Good books about space travel

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.