When authors fall in love with their own writing, watch out. Far too often, the books they single out as their favorites are among those least liked by readers. And this seems to be the case, at least for coauthor William Gibson, with The Difference Engine, the alternate computer history he co-wrote with fellow science fiction author Bruce Sterling. As Gibson writes in their joint afterword, “It’s the only novel with my name on it that I return to for reading pleasure.” God help us! The novel is a mess.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

They enjoyed writing this book. I didn’t enjoy reading it.

Gibson and Sterling are both successful authors. Both write well, although Gibson’s work is more colorful and more fluid. So, the words they use in this novel fit together nicely in sentences and paragraphs. Even whole pages. And they often paint a convincing picture of their reimagined mid-19th-century England, where The Difference Engine is set. The problem is, the story is garbled. The coauthors seem so intent on adding color and detail to the world they create that they make it godawful hard to follow the thread of the tale they’re telling.

Then, in the fifth of the book’s five very long chapters, they suddenly switch format. All of a sudden, they start trying to wrap up the story in a succession of “quotations” from documents and speeches. Unsurprisingly, the whole thing falls apart. Then, in their afterword, they add a shocker. Initially, they’d had trouble getting started on the project. But, Gibson writes, “Once we realized that the narrator is a computer, we stopped researching and started writing.” I found absolutely no hint that the narrator was a computer until I read that sentence in the final pages of the novel.

The Difference Engine by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling (1990) 512 pages ★★★☆☆

An overflowing cast of characters

New names surface with annoying frequency in The Difference Engine. But three are nominally the center of attention. We meet them, one at a time, each in their own long, long introductory chapter. They’re only tangentially related to one another, which is just one of the problems that surface on reading this novel. The connections become (more or less) clear only in the closing chapters. But, in fact, the star of this ill-conceived story is not a person at all but, as the title implies, a computer. An imagined, 19th-century version of a computer, but a computer nonetheless. Or, more properly, computers plural.

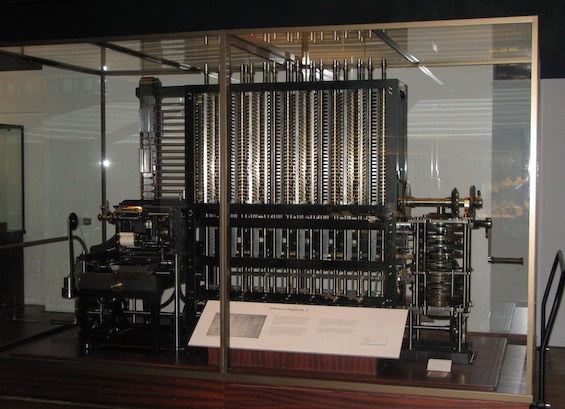

Much of this story hangs on the fantasy that Charles Babbage has built his “Difference Engine” and launched the digital age early in Queen Victoria’s reign. Now, just as today, computers are at work everywhere. They’re powered, like almost everything else, by steam. And, like the early mainframe computers of the 20th century, their tenders (or programmers) called clackers punch holes in cards that, fed into the machines, deliver data and instructions. But it’s one set of cards in particular that is truly the centerpiece of this story. Cards designed for one very special “engine”: the world’s largest computer. It’s called the Grand Napoleon, and it’s located in Paris. Somehow, never revealed, this set of cards has come to be called the Modus. And everybody seems to be all in a tizzy about it. I never quite figured out why.

Is this historical fiction? Alternate computer history?

According to the illuminati of the science fiction field, The Difference Engine is an early example of modern steampunk. (They usually cite Jules Verne and H. G. Wells as the originators of the genre.) But, not having a clue what the term meant, I simply assumed that the novel is a peculiar sort of historical fiction that is best described as alternate history.

However, the novel is a poor fit for the category, since the authors don’t answer a big “what-if” question with speculation about how the world might have been different had a decision been made differently or an event gone a different way. They’re all over the board. There’s little recognizable in the world Gibson and Sterling create here except for a few recognizable names. Charles Darwin, for example. And Babbage, of course. But the arrival of the digital age in England more than a century early is not the only big surprise. Others abound, among them the fact that the United States has somehow fractured into a truncated north, a Confederate South, and independent republics in Texas and California.

So, this is steampunk. But what IS steampunk?

So, for the benefit of the uninitiated (including me until recently), what is steampunk? Wikipedia’s definition seems clear. “Steampunk is a subgenre of science fiction that incorporates retrofuturistic technology and aesthetics inspired by 19th-century industrial steam-powered machinery. Steampunk works are often set in an alternative history of the Victorian era or the American “Wild West,” where steam power remains in mainstream use, or in a fantasy world that similarly employs steam power.” Fair enough. Thus, of course it’s clear that The Difference Engine is steampunk. But if this novel is anything like others in the genre, please don’t bother me with any more examples.

About the authors

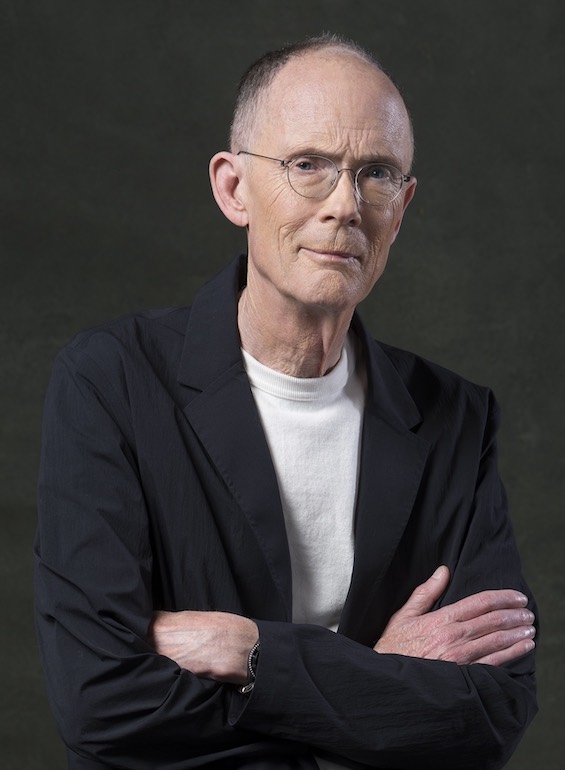

William Gibson

According to his author website, “William Gibson is credited with having coined the term “cyberspace” and having envisioned both the Internet and virtual reality before either existed.” But he rejects the suggestion he is a futurist with predictive powers. He claims he is a presentist who writes about the future to illuminate the present. Readers in the genre also credit him as the inventor of steampunk, citing The Difference Engine as the first novel in the category.

William Gibson was born in 1948 in Conway, South Carolina. He is the author of thirteen science fiction novels. Twelve of them constitute four trilogies. He has also written a very long list of short fiction as well as works in other categories, including screenplays and comics. Gibson now lives with his wife in Vancouver, British Columbia. He had moved to Canada as a young man in the 1960s and has remained there since.

Bruce Sterling

Bruce Sterling is one of the founders of the cyberpunk movement in science fiction. He is the author of twelve science fiction novels and ten collections of short stories. He has won the Hugo Award twice, among other honors. Sterling was born in Brownsville, Texas, in 1954, and grew up in Galveston until his family moved to India, where he lived for several years. He attended the University of Texas, where he received a degree in journalism. Sterling has lived overseas for extended periods.

For related reading

Since steampunk is not one of the categories I tend to read, I’ve associated this novel with the Great alternate history novels. Because, if it’s nothing else, it’s alternate history. Jumbled and unconvincing, but alternate history.

One of William Gibson’s novels, Neuromancer, won both a Hugo and a Nebula. And it’s often listed among the all-time best novels in the science fiction genre. But I tried reading it and got lost. Even on a second reading, the story seemed to me like so much nonsense. However, you’ll find it listed on both These novels won both Hugo and Nebula Awards and The ultimate guide to the all-time best science fiction novels.

You might also check out 10 top science fiction novels and 10 new science fiction authors worth reading now.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.