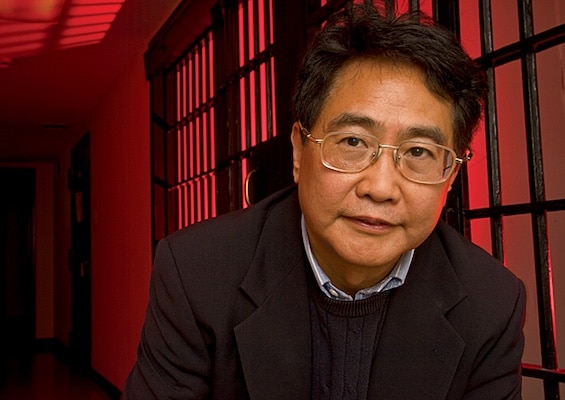

Beginning with Death of a Red Heroine in 2000, the Chinese American author Qiu Xiaolong inaugurated a series of Chinese detective novels now 13 strong and counting. I regard these books as the very best Chinese detective novels I’ve read. Qiu is a poet, translator, critic, and former professor of comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis. Oh, and he is also the Edgar Award-winning crime novelist of Death of a Red Heroine, which debuted this series.

A poet and professor as well as a detective novelist

Qiu traveled to the United States in 1988 on a Ford Foundation grant to work on a book about T.S. Eliot. This took him to Washington University, which Eliot’s grandfather had founded, and to St. Louis, where he has lived ever since. Though he had planned to return to Shanghai, the Tiananmen Square Massacre the following year convinced him of the need to remain. He feared imprisonment if he returned because of his strong foreign ties. Qiu enrolled at Washington University, which granted him both an MA and a PhD in Comparative Literature.

Investigations fraught with political complications

Qiu’s novels feature the singular figure of Inspector (later Chief Inspector) Chen Cao. Like Qiu himself, Chen is a published poet well known in literary circles. Although he had planned to pursue a different career, the Party steered him into the Shanghai Police Bureau. He soon became a “rising cadre” with great prospects for further advancement in light of his connections to top officials in Beijing.

Under the Party boss in the bureau, Chen runs the Special Investigations Squad. There, he and his assistant, Inspector Yu Guangming, pursue politically sensitive cases that his boss or officials in Beijing are unwilling to entrust to police officers who are not members of the Party. These difficult investigations often bring him into conflict with powerful forces within the party, the government, the “Mafias” and the tongs.

The heavy weight of the Cultural Revolution

Critics sometimes charge that Qiu’s plots are unimaginative, depending on devices familiar to mystery readers. While that may be the case at times, the novels serve not as formulaic mysteries but as windows into Chinese society and its modernization in the 1990s, 2000s, and beyond. Qiu frequently writes of the heavy burden that Mao’s Cultural Revolution laid on the shoulders of Chinese professionals and intellectuals—a burden that persists to this day in so many cases. And he details the many ways in which the Chinese Communist Party intervenes in the lives of citizens.

I’m in the process of reading the books in this series, one at a time. As I review each additional novel, I’ll post the result below in order. Stay tuned.

1. Death of a Red Heroine (2000) 477 pages ★★★★★—A gripping Chinese police procedural

You might think a police officer in any country in the world would share a great deal with anyone in law enforcement anywhere else. Surely, detecting crime and punishing criminals is a straightforward process that must involve the same methods everywhere. A Chinese police procedural must closely resemble one set in the United States or anywhere in Europe, right? But, while that’s all true to some extent, the assumption falls apart when the social and political conditions in which police officers operate are dramatically different. And Chinese-American author Qiu Xiaolong’s award-winning Chinese police procedural, Death of a Red Heroine, brilliantly dramatizes that point.

2. When Red Is Black (2005) 322 pages ★★★★☆—This gripping crime novel shows China in transition

Qiu paints a vivid picture of China in transition in When Red Is Black. When Inspector Chen is on vacation and a new case arises that demands quick action, his boss, Party Secretary Li, assigns Inspector Yu Guangming of Chen’s squad to take it on. Someone has murdered Yin Lige, a “dissident writer,” in her home, and Li insists Yu solve the case rapidly to forestall rumors and negative foreign press speculation that the government has murdered her. Of course, when the matter proves stubbornly resistant to solution, Inspector Chen will have no choice but to get involved as well. And the murder of Yin Lige now threatens to undermine his relationship with Party Secretary Li.

3. A Case of Two Cities (2006) 307 pages ★★★★☆—A detective investigates corruption in the Chinese Communist Party

Corruption plagues all authoritarian systems no matter how idealistic their origins may be. The absence of checks on the supreme ruler radiates downward throughout the system. Opportunities open up for officials high and low to abuse their authority for personal gain. And by the 1990s that pattern was clear to everyone in China. Corruption reigned in the Chinese Communist Party. From Zhongnanhai in Beijing to villages and towns throughout the country, wealth was accumulating in the hands of officials. In response, Party General Secretary Jiang Zemin launched China’s first nationwide anticorruption campaign. And an order from Beijing propels Chief Inspector Chen Cao into a high-stakes investigation into corruption.

4. A Loyal Character Dancer (2002) 368 pages ★★★★★—In a Chinese murder mystery, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution looms large

During the last ten years of his life (1966-76), Mao Zedong shut down China’s schools and universities, denying an education to a generation. At his urging, millions of Chinese teenagers and young adults turned instead to revolution. They upended life throughout their country in a frenzy of fanatical posturing and violence. In this so-called Cultural Revolution, those who were already “educated youth” were sent to rural villages to learn the ways of the people by working for years in menial jobs among the peasantry. The central characters in A Loyal Character Dancer, set in 1990, have all emerged scarred from this experience. And the legacy of the Cultural Revolution haunts them all. The book is both a masterful detective story and a thinly fictionalized history of China midway through its transition from Mao to Xi Jinping.

5. Red Mandarin Dress (2009) 324 pages ★★★★☆—As China changes, a serial murder case challenges the police and the Party

By 1997, China was midway between the era of Mao Zedong and that of Xi Jinping. In 1978, Deng Xiaoping had begun turning the country away from the planned, centralized economy dictated by Mao’s Leninist principles to “capitalism with socialist principles.” And Xi’s ascendancy to the supreme leadership was 15 years away in 2012. Those years between the two strongmen were a time of transition. And Qiu skillfully illustrates the stresses and dislocations of the period in his clever police mysteries featuring Chief Inspector Chen Cao. Red Mandarin Dress is especially revealing of the changes in Chinese society. It’s a serial killer tale against the backdrop of predatory capitalists supported by official corruption.

6. The Mao Case (2009) 302 pages ★★★★☆—Hunting the ghost of Mao Zedong in 1990s Shanghai

Mao Zedong is one of a handful of people whose image overshadows a broad swath of 20th century affairs. The others? Only Lenin. Stalin. Churchill. And Roosevelt. Yet we Americans know relatively little about the man. For example, Amazon lists ten times the number of biographies of both Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt as it does of Mao. And much of what is in print in English is heavily biased, painting “the Great Helmsman” as either a demigod or a scoundrel. Of course, any dispassionate reading of history shows that he was more the latter than the former, but in the end was both. And both sides of Mao’s complex personality come to life in Qiu Xiaolong’s historical mystery novel, The Mao Case. Like its predecessors, this novel is a superb example of historical fiction.

7. Don’t Cry, Tai Lake (2012) 273 pages ★★★★☆—Inspector Chen confronts environmental crime in a Chinese city

Anyone who’s even dimly aware of events in China today understands that the country faces a host of pressing environmental challenges. For example, more than 100 of its cities languish under clouds of lethal air pollution. And “as much as 90% of the country’s groundwater is contaminated by toxic human and industrial waste dumping.” The latter is the underlying theme in the seventh novel in Qiu Xiaolong’s uniquely original series of mysteries featuring Chief Inspector Chen Cao. When ordered to take a vacation on a lakeshore in the city of Wuxi (WOO-shee), he stumbles into a murder case that involves chemical dumping in the famously crystalline lake, now overgrown with green algae. Working undercover, Chen works with a local policeman to solve the murder. Meanwhile, he takes steps to expose the criminal dumping that has despoiled the lake.

8. Enigma of China (2013) 288 pages ★★★★☆—Politics intrudes as Inspector Chen investigates corruption

No large institution is free of corruption. The temptation to gain personal wealth or power is too great for some individuals to ignore. Of course, the incidence of self-dealing may be lower in business organizations engaged in fierce competition. Corruption adds costs that top executives are usually inclined to eliminate. The same may be true in democratic institutions where checks and balances abound. But in any one-party system, endemic corruption is inevitable. The histories of Russia, India, Mexico—and China—bear out this truth. And Chinese corruption is especially dramatic. Today, President Xi Jinping confronts it at every turn, no matter how many “anti-corruption” campaigns he may mount. Widespread corruption, from the very top to the village level, has been a reality in China for centuries. And Qiu Xiaolong explores that theme as it appeared early in this century in Enigma of China.

9. Shanghai Redemption (Inspector Chen Cao #9) by Qiu Xiaolong (2014) 321 pages ★★★☆☆—A top Chinese police detective struggles to survive an attack from the Party

Homicide detective Chen Cao has risen to the formidable posts of Chief Inspector, head of the Special Investigations Squad, and Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party in the Shanghai Police Bureau. Inspector Chen is that rarity in Chinese law enforcement: an honest man who seeks only the truth, wherever it might lead. He has resisted official pressure to avoid findings that might embarrass powerful officials. But now, suddenly, the axe falls from somewhere above. Chen receives a “promotion” to a make-work job outside the police, Chairman of the city’s Legal Reform Committee. Somebody close to the top wants to steer him away from one of the several new cases assigned to the Special Investigations Squad. But who is pulling the strings? And which case poses a threat to the official’s hold on power? This is the setup in Qiu Xiaolong’s Chinese detective thriller, Shanghai Redemption.

For related reading

Check out The 8 best historical mystery series and 30 insightful books about China.

You might also enjoy my posts:

- The best mystery series set in Asia

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

- The best police procedurals

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- Top 20 suspenseful detective novels

And you can always find the most popular of my 2,400 reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.