Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

You might think a police officer in any country in the world would share a great deal with anyone in law enforcement anywhere else. Surely, detecting crime and punishing criminals is a straightforward process that must involve the same methods everywhere. A Chinese police procedural must closely resemble one set in the United States or anywhere in Europe, right? But, while that’s all true to some extent, the assumption falls apart when the social and political conditions in which police officers operate are dramatically different. And Chinese-American author Qiu Xiaolong’s award-winning Chinese police procedural, Death of a Red Heroine, brilliantly dramatizes that point.

A young police inspector takes on a case he doesn’t want

The novel opens in Shanghai in 1990, a time when China was in transition from the rigid egalitarianism of its past to a time when billionaires could openly flourish. Chief Inspector Chen Cao has risen to head the special case squad of the Shanghai Police Homicide Division. He’s only in his early thirties and has aroused envy and resentment among many of his colleagues for his rapid rise in the ranks. But when the dead, naked body of a young woman turns up in a canal in the outskirts of Shanghai, it’s Inspector Chen who must take on the unwanted case. She has been strangled, but there is absolutely no clue to her identity. The case appears to be a loser.

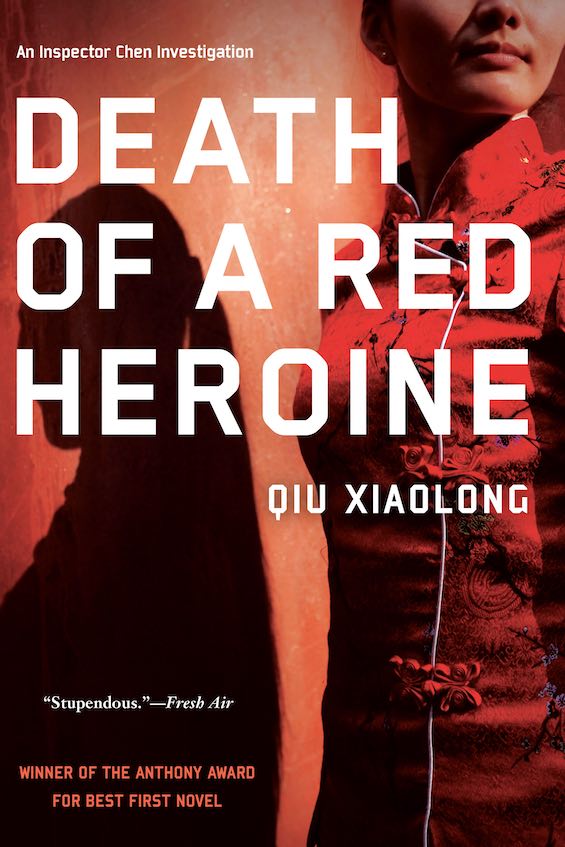

Death of a Red Heroine (Inspector Chen #1) by Qiu Xiaolong (2000) 477 pages ★★★★★

Winner of the Anthony Award for Best First Novel

A Chinese police procedural true to the country’s history

Death of a Red Heroine is a police procedural that’s faithful to the genre. We follow Inspector Chen and his tiny staff through weeks of meticulous efforts to uncover the identity of the dead woman and any clues to why anyone might have murdered her. For the police, it’s all tedium, and frustrating. Eventually, however, a breakthrough comes from an unexpected quarter. And to the officers’ horror, they discover that the young woman is Guan Hoangying, a “national model worker” who has gained fame throughout China for her selfless dedication to her job and to the Communist Party.

Troubling political aspects of the case

Guan Hoangying only heads the cosmetics department at a popular Shanghai department store but has become a national celebrity in the manner of the Stakhanovite workers of Stalin’s Soviet Union. In translation, her name means Red Heroine: “Guan . . . for closing the door, Hong for the color red, and Ying for heroine.” And that is what she is to millions of Chinese. Which means that the case now has become political. The upshot is that Chen’s superiors are now looking over his shoulder—and meddling at will.

More weeks pass as Inspector Chen seeks in vain for the reason anyone might have wished her dead, much less the identity of the killer. Eventually, though, that information turns up as a result of the dogged work of the special case squad. And the answers they uncover at length raise even more troubling political complications. Because the suspect is an “HCC,” the son of a High Cadre in the Party. And that means Chen will completely lose control of the case.

The inspector is a published poet and a translator

Inspector Chen is a remarkable man who stands out for many reasons other than his youth. He is a published poet credited with distinction as a modernist. The son of a well-known professor of the Neo-Confucian school, he majored in English literature and now translates Western mystery novels to supplement his meager salary as a police inspector. He is, of course, a Communist Party member, since he could not otherwise have risen so far or so fast. But so are many others in the police hierarchy. For reasons that are unclear to him, the Communist Party Secretary in the Homicide Division, Li Guohua, had arranged for his promotion. In the NYPD, Li would be known as Chen’s “rabbi.” And the older man’s support will prove crucial as the inspector’s investigation founders and faces rising opposition to his methods.

A city, and a country, in rapid transition

Qiu’s novel is a study of China in transition. In 1978, a dozen years before the time in which the story is set, Deng Xiaoping had inaugurated the country’s move toward a market economy. The change was well underway by 1990. And its consequences were becoming clear. The previous year, the People’s Liberation Army had massacred as many as several thousand young protestors at Tiananmen Square, signaling Deng’s unwillingness to allow the change to undermine the primacy of the Communist Party. And his action exacerbated the ongoing debate between the conservative “old cadres” and younger reformers. It’s this debate that complicates—and threatens—Chief Inspector Chen’s investigation of Guan’s murder.

Shanghai in 1990 would be unrecognizable today

Shanghai today is one of the world’s largest cities, crammed with artfully designed high-rise buildings and shops offering the world’s finest luxury goods. It’s China’s financial center and accounts for an enormous share of the country’s economic activity. In 1990, the old, colonial city was making way for the new. Bulldozers and construction cranes were everywhere. The streets were still crammed with bicycles but, increasingly, bike-riders were threatened by the fast cars imported by “high cadres” and the growing number of successful businessmen.

For a sense of the change Chief Inspector Chen witnesses as he pursues his “HCC” suspect, consider the following table:

| What | 1978 | 1990 | 2020 |

| Shanghai population | 5.6 million | 8.6 million | 28.5 million |

| Chinese exports | $6.8 billion | $49.1 billion | $2,723 billion |

About the author

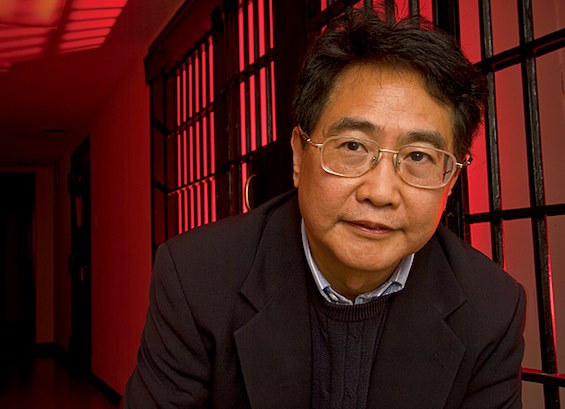

Qiu Xiaolong was born in Shanghai in 1953. He received a BA in English and an MA in English Literature from universities in China and worked for two years as an associate professor at a third institution. Qiu traveled to the United State in 1988 to research a book on T. S. Eliot at Washington University in St. Louis under a Ford Foundation grant. Following the Tiananmen Square massacre in June 1989, he remained in the US to avoid persecution by the Chinese Communist Party. He received an MA and PhD in Comparative Literature from Washington University and joined the faculty there. He and his family still live in St. Louis.

For related reading

You’ll find the sequel to this novel at A Loyal Character Dancer (In a Chinese murder mystery, the legacy of the Cultural Revolution looms large). The third book is When Red Is Black (This gripping crime novel shows China in transition).

This novel is one of The best mysteries and thrillers of 2022.

Check out 30 insightful books about China.

You might also enjoy my posts:

- Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

- Top 20 suspenseful detective novels

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.