One of the best ways I’ve found to explore the factors that influence the grand sweep of modern history is to examine the stories of individual companies, industries, and commodities. And among the books I’ve found that have helped the most are The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization by Vince Beiser, Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert, and Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism by Bartow J. Elmore. Now chocolate joins sand, cotton, and Coke as a key to explore the depths of business history: Deborah Cadbury‘s Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World’s Greatest Chocolate Makers. Herself a descendant of the illustrious Quaker family that built one of the world’s biggest chocolate manufacturers, Cadbury provides an intimate view of an extraordinary company that pioneered a radical new approach to business.

Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World’s Greatest Chocolate Makers by Deborah Cadbury (2010) 386 pages ★★★★★

Shareholder value versus stakeholder capitalism

The modern corporation began taking shape late in the nineteenth century. But only in the past four decades or so has it evolved into the form we recognize today in the United States—a massive, often highly diversified enterprise driven by “shareholder value” and run by professional (often grossly overpaid) managers. Under the precepts of shareholder value, the directors and managers of an enterprise regard it as their overarching duty to deliver ever-rising stock prices to those who “own” the company. In practice today, this means they look to the quarterly profit statements demanded by Wall Street and the City of London as the true measure of their success.

Business wasn’t all about money in the 19th century

In the mid-nineteenth century, when Cadbury and other Quaker-owned chocolate companies were laying the foundation for their future wealth, business was still largely a personal affair. Companies were owned and run by the families of their founders, many were managed paternalistically, and they were closely tied to the communities where they were located.

The “chocolate Quakers” were outliers

But the Quakers who built the early chocolate industry were outliers in their unwavering commitment to quality and the welfare of their employees. They “believed that ‘your own soul lived or perished according to its use of the gift of life.’ For them, spiritual wealth rather than the accumulation of possessions was the ‘enlarging force’ that informed business decisions.” The approach they took to their businesses is what today we would call “stakeholder capitalism“—a commitment to make business decisions based on how they would affect all stakeholders, not just those who own the shares.

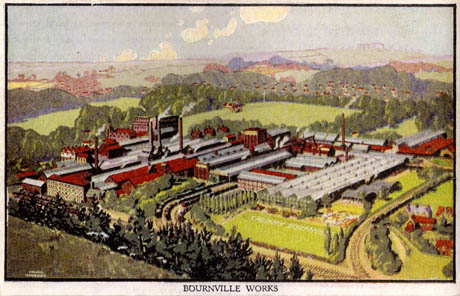

The revolutionary new rural factory Cadbury built to move

its workforce out of the slums. Image credit: Edible Geography.

Yes, there were chocolate wars—twice

Chocolate Wars follows the trajectory of Cadbury and other chocolate manufacturers founded in Britain by Quakers in the nineteenth century. These pioneering companies have long since been absorbed into immense, multinational corporations that have shed the humane Quaker values on which they were grounded. A century and a half ago, Cadbury (founded 1824), Rowntree’s (founded 1862), and Fry’s (founded 1761) accounted for the lion’s share of chocolate sales in the United Kingdom. Here’s what happened to them:

- Fry was absorbed by Cadbury and later disappeared entirely.

- Today, Rowntree’s is part of Nestlé, the Swiss multinational that is the largest food company in the world.

- And Cadbury is wholly owned by Mondelez International—a business once called Kraft Foods—and is the world’s second largest confectionary company after US-based Mars, Incorporated.

The eponymous “chocolate wars” can refer to the usually decorous rivalry among the big three British companies in the nineteenth century. But more often it’s taken to mean the no-holds-barred struggle for dominance in the twentieth century primarily involving the Swiss (Nestlé), Americans (Mars and Hershey), and British (Cadbury and Rowntree).

Even if you’re unfamiliar with the company names, you’ve surely come across—and quite likely consumed—some of their leading brands: Cadbury’s Dairy Milk; Rowntree’s Kit Kat and Rolo; Hershey’s Hershey Bar and Hershey’s Kisses; Nestlé’s Nescafé and infant formula; and Mars’ M&Ms, Milky Way, and Snickers.

A cast of larger-than-life characters in Chocolate Wars

The principal characters in Cadbury’s account are a fascinating lot.

George and Richard Cadbury

George Cadbury (1839-1922) and Richard Cadbury (1835-99) were the younger sons of their company’s founder John Cadbury, who took over a failing business in 1861 and built it into a behemoth. Along the way, they constructed a model village-factory at Bournville, which remains the Cadbury headquarters to this day. They were both exceedingly generous philanthropists who believed the causes they supported were more deserving of their accumulated wealth than their children—and the children agreed.

Joseph Rowntree

Joseph Rowntree (1836-1925) was the Quaker industrialist and philanthropist from York who ran Rowntree’s, one of the Cadburys’ principal competitors. Rowntree was an active social reformer who founded several trusts to improve the quality of life of his employees.

Forrest Mars Sr.

Forrest Mars Sr. (1904-99) was the hard-driving force behind the Mars candy empire. After his erratic father forced him out of the business they’d built together, Mars built his own company and eventually absorbed the old firm. Mars’ values, and those of his family, are far removed from the ideals that motivated the Quakers. The family is widely reported to have been instrumental in the repeal of the estate tax in the United States—the antithesis of the attitudes that drove the Cadburys and Rowntrees.

Milton Hershey

Milton Hershey (1857-1945) pioneered the manufacture of caramel, then built a new company that was the first to mass-produce milk chocolate. He built the model town of Hershey, Pennsylvania and gifted his controlling interest in the Hershey Company to a trust. The philanthropy benefits the Hershey Industrial School (now the Milton Hershey School) he had founded there for underprivileged orphan boys. The trust remains the controlling shareholder of Hershey’s to this day. Hershey’s values were grounded in the Mennonite faith of his parents and of the community where he grew up, Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

What these remarkable men have in common is the extraordinary persistence they brought to their work. Every one of them struggled for many years against often great odds to develop the products and build the businesses that would ensure their future.

Reourceful and inventive Swiss, Dutch and French entrepreneurs also enter into Chocolate Wars, notably Henri Nestlé, Daniel Peter, Rodolphe Lindt, Jean Tobler, Coenraad Van Houten, and Johan Rudolf Sprüngli. You may recognize most of their surnames, too, in some of the other products you’re likely to encounter if, like me, you’re a chocoholic.

Family ownership is (mostly) long gone in the chocolate industry

But the days of family ownership and management have long gone by the wayside in the chocolate industry, with the exception of Mars, Inc., which remains family-owned. “When Dominic [Cadbury] stepped down in 2000, for the first time in the firm’s 170-year history, there was no longer a member of the family on the board, and less than 1 percent of [the] shares were in family hands. Over the years, the shares held by the Cadbury benevolent trusts had also declined.”

This is solidly grounded business history

Deborah Cadbury has done a superb job relating this complex tale in such a readable and insightful way. Chocolate Wars is solid business history. In nearly 400 pages, I came across only one error. She notes, in explaining the discrimination still directed at Quakers in Victorian England, that university education was not open to them. Both Oxford and Cambridge then denied entry to Quakers, Nonconformists, and Jews, as she correctly notes. However, University College, London was founded in 1826 with the express purpose of admitting students regardless of their religion.

About the author

British author and documentary filmmaker Deborah Cadbury is the author of ten nonfiction books and the producer of more than a dozen documentary films and television series, for which she has won many international awards. In Chocolate Wars, she refers to “the chocolate branch of the family.” She is a descendant of the oldest son of John Cadbury, who founded the original company that much later grew into Britain’s largest confectionary business. She is not herself affiliated with the company.

For related reading

This is one of My 10 favorite books about business history.

I have also reviewed The School that Escaped the Nazis: The True Story of the Schoolteacher Who Defied Hitler by Deborah Cadbury (The Holocaust viewed through the eyes of children).

Recently I reviewed another fascinating book about the merchandising of food: The Secret Life of Groceries: The Dark Miracle of the American Supermarket by Benjamin Lorr (An investigative journalist tackles the American supermarket).

Check out:

- The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization by Vince Beiser (We never think about it, but our civilization is built on sand)

- Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert (Capitalism reexamined from an historical perspective)

- Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism by Bartow J. Elmore (Big Soda unmasked: it’s not as sweet as you think)

You might also enjoy 20 top nonfiction books about history.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.