Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace is sometimes called the greatest novel ever written. But I’m not sure why. For its time—the first edition appeared in 1869—it must have been remarkable for the stark realism of its depiction of soldiers at war. But War and Peace isn’t a novel in the truest sense, and it doesn’t wear well in the 21st century. It’s a curious mixture of narrative, historical commentary, and philosophy as well as action scenes and dialogue. The fictional passages are often brilliant—especially the battle scenes. By contrast, much of the rest is barely readable. Particularly in its concluding chapters, the text is wordy, repetitious, and tedious. Nowadays a thoughtful editor would likely cut back this 1,200-page doorstopper to four or five hundred pages.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Napoleon invades Austria, and Russia fumes

Apart from then-Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte, this story revolves around five noble Russian families—the Bezukhovs, the Bolkonskys, the Rostovs, the Kuragins, and the Drubetskoys. Four individuals emerge as central characters: Count Pyotr Kirillovich (“Pierre”) Bezukhov; Prince Andrei Nikolayevich Bolkonsky; Prince Andrei’s sister, Princess Marya Nikolayevna Bolkonskaya; and Countess Natalya Ilyinichna “Natasha” Rostova. But don’t be fooled by the titles. They’re not royalty, just very rich people.

Tolstoy tells his story in four parts spanning fifteen years. The first part, encompassing Books One through Seven, covers the years 1805 through 1810. We meet the central characters in the whirl of high society in St. Petersburg and Moscow and on the march to confront Napoleon. We follow the titanic struggle between Napoleon’s Grand Armée and the allied Russian and Austrian armies when the French invade Austria. Tolstoy dwells in detail on the decisive Battle of Austerlitz (December 2, 1805), where Napoleon’s 68,000 troops humiliate 90,000 Russians and Austrians. The tale continues through the following five years as France and Russia eventually make peace and the lives of the families at center-stage become more intertwined.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869) 1,225 pages ★★★★☆

Napoleon invades Russia, and meets his comeuppance

In part two, including Books Eight through Fifteen, Napoleon invades Russia with an army of nearly half a million. It’s a multinational force, including Poles, Italians, Germans, Swiss, and Spanish troops. French-speakers were a minority. While the balls and home visits and gossip continue among the aristocracy in St. Petersburg, insulated from the war, the invaders rapidly push deeply into the countryside. Tolstoy depicts the fighting through the experiences of the young men of the five prominent noble families at the center of the story. Prince Andrei Bolkonsky, Count Pyotr Bezukhov, Natasha Rostov’s brother, Nikolai, and others participate in the most crucial engagements. But most of the action revolves around the crucial Battle of Borodino (September 7, 1812) at the approaches to Moscow. Although in many ways Borodino was a Russian victory because they killed so many of the invaders, many historians regard it as Napoleon’s triumph, because it allowed him to occupy Moscow.

Napoleon is history, and Russian society grows more conservative

The third part of the novel encompasses the First Epilogue, covering the years 1813-20, and the Second Epilogue, which consists entirely of Tolstoy’s musings on war, history, cause and effect, and free will. The narrative in the first epilogue follows the five families through the later phase of Tsar Alexander I‘s reign (1801-25). During his early years on the throne, Alexander was regarded as a liberal. But as all Europe moved rightward in the wake of Napoleon’s defeat, Alexander begins to shed his youthful pretensions to reform. (His younger brother and successor, Nicholas I, was a notorious reactionary.) But for the aristocracy, these changes in sentiment at the top make little difference. They continue to live their lives in opulence and dissolution, their whims and expensive tastes underwritten by millions of serfs held in bondage on their estates.

Tolstoy’s views on history and war

Tolstoy makes abundantly clear from the outset that he takes a dim view of all things military. The great European generals of Europe early in the nineteenth century—French, Austrian, German, Russian—mostly come off as puffed-up fools who delude themselves into thinking that their orders determine the course of events. Their officers and men usually find the orders are impossible to carry out, or they simply ignore what they’ve been told to do. But Tolstoy treats the overall Russian commander, Mikhail Kutuzov, more gently. In fact, he seems wise, in the author’s telling. But he is an obese old man in failing health who falls asleep at odd times and can barely ride a horse. His subordinates frequently defy him—and thousands of Russian soldiers die as a result.

Napoleon Bonaparte comes off especially poorly. Again and again, Tolstoy makes a mockery of his reputation as a military genius. He compares the brilliant general to a bold sheep leading his flock to doom. “Chance, millions of chances, give him power, and all men as if by agreement co-operate to confirm that power.” But ultimately that power means little. Napoleon is a fool, believing that events happen because he wills it. Without naming the Great Man Theory of History, which held sway throughout the nineteenth century, Tolstoy repeatedly ridicules it. He questions whether the actions or commands of any individual can affect the course of history. Yet he also rejects the countervailing theory that ideas are “the force that drives nations.” History is no science. It is the will of God, and no earthly force, that sets events in action. So Leo Tolstoy would have us believe.

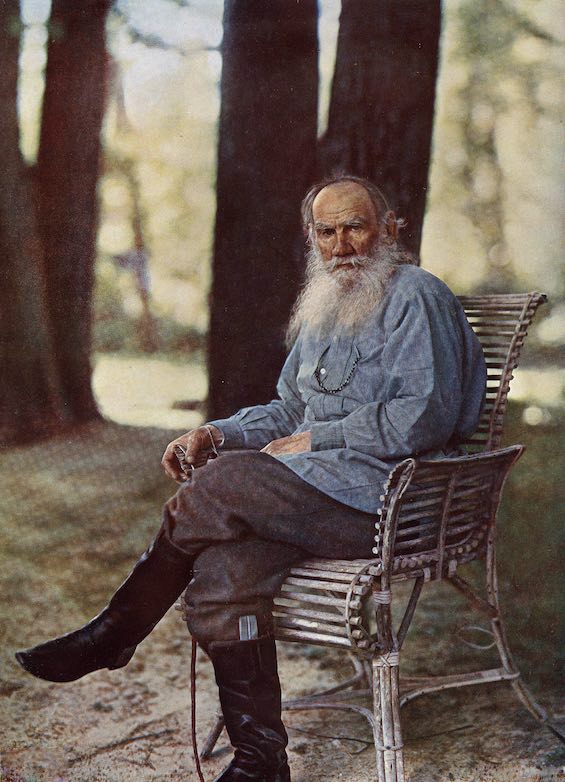

About the author

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) is best known for his two longest novels, War and Peace and Anna Karenina. Both are widely regarded as among the finest novels ever written. As Britannica observes in its entry on the author, “The scion of prominent aristocrats, Tolstoy was born at the family estate, about 130 miles south of Moscow, where he was to live the better part of his life and write his most-important works.” (The image above was created there.) His writing career encompassed more than sixty years (1847-1910). During those long years, Tolstoy wrote innumerable novellas, short stories, plays, articles, essays, philosophical works, fables and parables. He fathered thirteen children, eight of whom survived childhood. His great- and great-great-grandchildren hold a number of prominent posts in Russia today.

For related reading

This is one of the Great war novels.

You might also check out 20 most enlightening historical novels and Top 10 great popular novels.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.

Hi, Mel: I’d suggest you read “Don Quixote,” a great novel. (& funny —which Tolstoy never was.) Karen F.

Been there, done that. Decades ago. But thanks.

BTW, the name’s Mal, not Mel.