The surprises start on page three. “If one of our distant ancestors hadn’t been infected by a virus hundreds of millions of years ago,” Jonathan Kennedy writes, “humans would reproduce by laying eggs.” In Pathogenesis, Professor Kennedy sketches the often-decisive role of infectious diseases from the emergence of life on Earth to the COVID-19 pandemic. But microbial invaders haven’t just swayed the course of human history. They have played a central role in determining how we have come to be who we are. “Infectious diseases have killed so many people throughout history,” Kennedy asserts, “that they are one of the strongest forces shaping human evolution.”

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

“An alternative way of looking at the world”

In centuries past, historians contrasted the Great Man Theory of History with what one French historian “history from below and not from above,” citing the influence of mass movements and intellectual currents. These days, most historians recognize that neither approach is sufficient to explain the past. But Kennedy rejects both. “The idea of history from below is much more inclusive than the worship of a few heroic individuals,” he writes, “but still it focuses on humans as the driving force of history.” Instead, he proposes “an alternative way of looking at the world” based on “the realization that microbes play a much more important role than we would have believed just a few years ago.” And he cites recent advances in paleontology and genetic science to prove his point.

Pathogenesis: A History of the World in Eight Plagues by Jonathan Kennedy (2023) 336 pages ★★★★★

This book will change how you view history

The more you know about the 300,000-year story of humankind, or any historical era, Jonathan Kennedy will surprise you. And he will do it again and again. He makes a truly compelling case about how disease shaped history. Consider just these two examples among more than I can count.

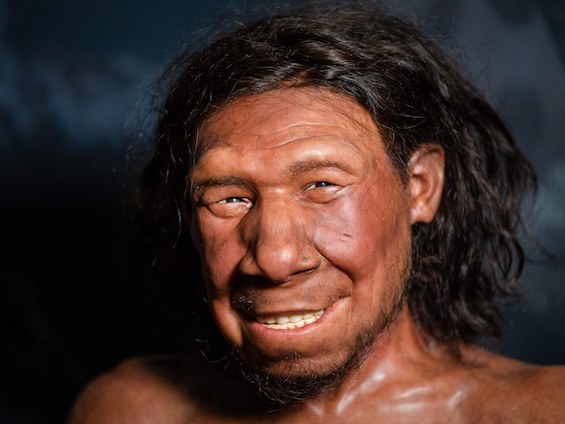

How Homo sapiens drove all other species of humans to extinction

It’s well known that Europeans carried deadly diseases to the Americas and wiped out as many as 90 percent of the indigenous population throughout the Western Hemisphere. Something similar happened when Homo sapiens met the Neanderthals. And our species won the day, not because our ancestors were smarter, had better weapons, or were more sophisticated. It turns out that they had none of these advantages. They triumphed because they harbored infectious diseases.

Microbes were abundant in humanity’s homeland in Africa. Thus, Kennedy tells us, “Homo sapiens, whose ancestors had lived in Africa for millions of years, carried a far greater disease load than Neanderthals, who had inhabited Europe for hundreds of thousands of years.” Neanderthals had left Africa long before the Last Glacial Period began around 110,000 years ago and had evolved in Europe’s frigid climate, where infectious diseases were few. The same was true of the Denisovans and other human species. And when the species met, the result was foreordained. Our ancestors “encountered Neanderthal and Denisovan communities that had never been exposed to African pathogens and hadn’t had the opportunity to build up any tolerance. Within a relatively short period of time all other human species died out and were replaced by the newly ubiquitous Homo sapiens.”

How Islam built a great empire

“Without the lethal effects of Yersinia pestis [which causes plague],” Kennedy writes, “it is almost impossible to imagine that Islam would have blossomed from a sect with a small group of followers in the Hijaz to a major religion practiced by almost a quarter of the world’s population, or that Arabic would have gone from being the language of a few desert tribes to one that is now spoken by almost half a billion people across North Africa and the Middle East.” Plague, it turns out, was a necessary though not sufficient explanation.

In the early years (622-632 CE) of Islamic expansion, two great empires dominated the Middle East. The Sassanian Empire was based in present-day Iran. Its centuries-long rival was the Byzantine Empire (the Eastern Roman Empire), centered on Constantinople (today’s Istanbul). For a quarter-century (602-628 CE), the two empires had fought a devastating war. They exhausted themselves, and nearly emptied their treasuries. Those factors weakened them greatly. But the spread of plague throughout the region was the coup de grace. So, when Arab armies moved northward from the desert, where plague was absent, they met foes incapable of strong resistance. Islam conquered Persia and grabbed a huge chunk of Roman territory in the Middle East.

Something similar took place to enable the rise of Christianity. But that’s another story.

Two more examples of how disease shaped history

Slavery

“The emergence of American slavery and the ideology of racism used to justify it had a great deal to do with infectious diseases and who could, or could not, survive them.” Hard to believe? Believe it! Spanish, Portuguese, British, and French colonialists all tried running plantations with non-African labor. But all their workers (mostly indentured laborers) fell victim to malaria and other potentially lethal diseases. Only the few African slaves imported at first fared better. And as their numbers increased, racist ideology evolved to justify their enslavement. (Yes, the slavery came first, then, only later, the racism.)

American independence

American rebels won the Revolutionary War despite overwhelming odds for several reasons, including support from French warships and soldiers. But the reason at the decisive moment in 1781 was that in British General Cornwallis’ army at Yorktown in 1781 “over half of the soldiers under his command were unable to fight due to falciparum malaria.” That’s the most lethal form of malaria, and it was endemic in the American South until the 1930s. (It’s coming back again.) The colonists had survived the disease and developed partial immunity. The British hadn’t. And as a result, Cornwallis was utterly defeated. Which convinced the British that their war against American independence was futile. Peace negotiations followed quickly.

About the author

Professor Jonathan Kennedy describes himself on his web page at Queen Mary University in London as follows: “I am a Reader in Politics and Global Health in the Centre for Public Health and Policy. I am also co-Deputy Director of the Centre for Public Health & Policy. My research use insights from sociology, political economy, anthropology and international relations to analyse important public health problems. For example, my research has explored the link between populist politics and vaccine hesitancy in Europe, the negative impact of the CIA drone strikes on polio eradication efforts in Pakistan, and how Saudi-led bombing of Yemen resulted in the world’s worst cholera outbreak in 2017.

“I obtained my PhD in sociology from the University of Cambridge (2013). Prior to joining Queen Mary, University of London in 2016, I taught international development at the Department of Political Science, University College London and worked as a research associate at the Department of Sociology, University of Cambridge.”

For related reading

I’ve read and reviewed many books about pandemics. You’ll find them at Books about COVID-19 and other pandemics.

For a contrary view of human origins, see Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, by Yuval Noah Harari (Exploring the arc of history over 70,000 years). And, for a book Kennedy repeatedly cites in his own book, see Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States by James C. Scott (This book will challenge everything you know about ancient history).

You’ll also find books that will add greater depth at:

- Gaining a global perspective on the world around us

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.