Learning to read Chinese can be a monumental challenge for almost anyone—including the Chinese. There is no alphabet. In fact, there is really no single language called Chinese, which is a family of languages and dialects, many of which are mutually unintelligible.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Written Chinese is, for the most part, the same across all languages and dialects that outsiders might call Chinese. But pronunciation varies widely and sometimes meaning as well. Even within a given dialect, a single character may have multiple meanings. And the inventory of printed Chinese characters (ideographs) is staggeringly large. All told, there are more than 50,000 characters, and thousands more have surfaced in recent years.

How, then, could anyone not a native speaker possibly master the language? More to the point, how can anything written in Chinese be accurately translated into another language? Or converted into the 1’s and 0’s of the language of computers? In Kingdom of Characters, Yale professor Jing Tsu tells a remarkable story. It’s the tale of the brilliant men who engineered the Chinese language revolution.

Kingdom of Characters: The Language Revolution that Made China Modern by Jing Tsu (2022) 337 pages ★★★★☆

The Chinese language revolution

Jing Tsu’s tale begins at the turn of the 20th century. For a short time before the Empress Dowager Cixi put a stop to calls for change, a reform movement had flowered in China in the wake of the country’s humiliation in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-5. One of the highest priorities of the reformers was to simplify and unify the Chinese language. After all, “if China couldn’t communicate with the rest of the world, it was because China was also struggling to communicate within its borders.” Then, only “30 to 45 percent of the men and from 2 to 10 percent of the women in China knew how to read and write.” Although the reformers at court were in disgrace, ambitious scholars worked diligently in the ensuing years, trying first one approach, then another, to make the language more accessible by simplifying the characters.

Many of these language reform efforts involved communications technologies. Inventors labored for decades to develop a workable Chinese-language typewriter. Other scholars devoted years of struggle to endless negotiations with Westerners to make it possible for Chinese-language messages to be transmitted by telegraph. Yet others focused on classifying Chinese characters to permit librarians to rank and catalog the country’s immense store of knowledge. And over the decades, all these efforts gradually bore fruit by the time the Revolution triumphed in 1949.

But the biggest changes of all came later.

The pivotal role of Mao Zedong

Westerners typically view Mao Zedong as a man without redeeming qualities. After all, he was responsible for the unnecessary deaths of at least 30 million Chinese as a result of the draconian policies he imposed in the 1950s and 60s. In China, however, Mao is still revered by many. And one of the reasons China’s current leader Xi Jinping has “resurrected” him was the pivotal role he unknowingly played in easing China’s entry into the world community.

“At the founding of the PRC,” Jing Tsu writes, “more than 90 percent of the country was still illiterate and communicated in regional dialects.” Putonghua, or Mandarin, had become the country’s official language in 1911 in the republican revolution that overthrew the Qing Dynasty. But relatively few spoke it, and Mao set out to change that. Ironically, he “didn’t speak a word of Putonghua,” which was the language of scholars and the court, not the common people. Yet he imposed it on the country to ease the drive for universal literacy.

A drive for universal literacy

As Jing Tsu reports, Mao “guided the Chinese language through its two greatest transformations in modern history. The first was character simplification, which would reduce the number of strokes in more than 2,200 Chinese characters. The second was the creation of pinyin, a standardized phonetic system using the Roman alphabet and based on the pronunciation of Putonghua (“pinyin,” which means “to piece together sound”).

“The rate of illiteracy began to decline under the twin implementation of character simplification and pinyin. By 1982, the literacy rate for people over age fifteen nationwide had risen to 65.5 percent, and it reached 96.8 percent in 2018.” The move to Mandarin and the simplification of the written language at length also made it possible for a later generation of language experts to convert Chinese characters into the 1’s and 0’s of the digital era. You know the rest.

An important and inspiring story

In Kingdom of Characters, Jing Tsu tells an important and inspiring story. She bases her account on the lives and work of the fascinating individual scholars and officials who played central roles in the process. From time to time, however, the tale becomes bogged down with technical detail. Necessarily so, but it doesn’t make for easy reading throughout.

About the author

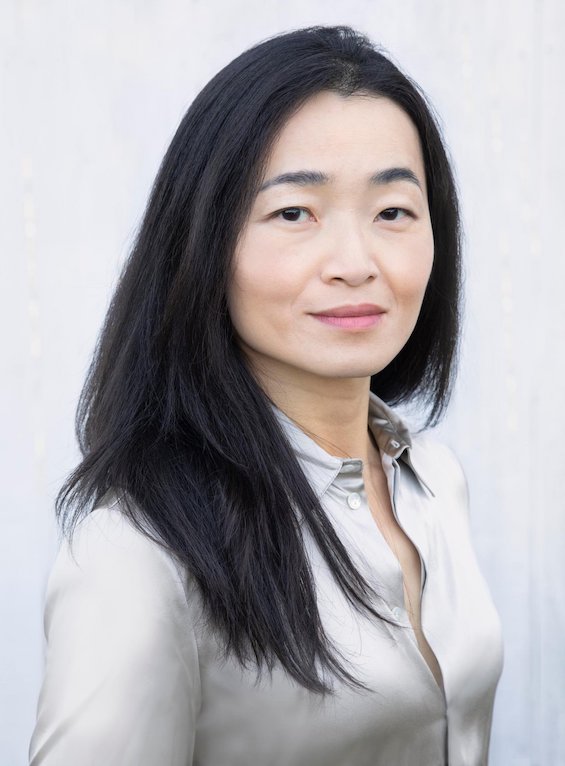

According to her biography at Yale University’s Department of Comparative Literature, Jing Tsu “specializes in modern Chinese literature & culture and Sinophone studies, from the 19th century to the present. Her research spans literature, linguistics, science and technology, typewriting and digitalization, diaspora studies, migration, nationalism, and theories of globalization.” This account of the Chinese language revolution is her fifth book.

For related reading

This title is featured on Good books about dictionaries, libraries, and language.

Check out the 10 best books about innovation.

For more information about the dynamics of language, see:

- Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries, by Kory Stamper

- The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams

You might also be interested in 30 insightful books about China.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.