In May 2019, my wife and I spent three days in Rwanda’s charming capital city, Kigali, on a side trip from a visit to Kenya. We were enchanted by the rolling hills and by the spotless, flower-lined streets and sidewalks that conjured up memories of Singapore. At the Kigali Genocide Memorial, we walked slowly in shocked silence through the garden planted over the bodies of 250,000 victims of the 1994 massacre. In writing about the visit to friends at home, I rhapsodized about Rwanda’s explosive economic growth rate—the highest in Africa and nearly equal to China’s—and likened President Paul Kagame to a “benevolent dictator.” In fact, the impression I gained in Kigali represented the consensus Western view of Rwanda.

I got it all wrong

Sadly, I got it all wrong. And so has a generation of diplomats, international bureaucrats, aid officials, and philanthropists who have poured billions into the regime of that “benevolent dictator.”

Because President Paul Kagame is no philosopher king. The economic statistics are inflated. And those 250,000 bodies are all Tutsis like the President and nearly everyone else in his regime. They do not include any of the hundreds of thousands of Hutus that Kagame’s army murdered in revenge when they liberated the country from the génocidaires. It all comes to light in veteran foreign correspondent Michela Wrong’s shocking exposé, Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad.

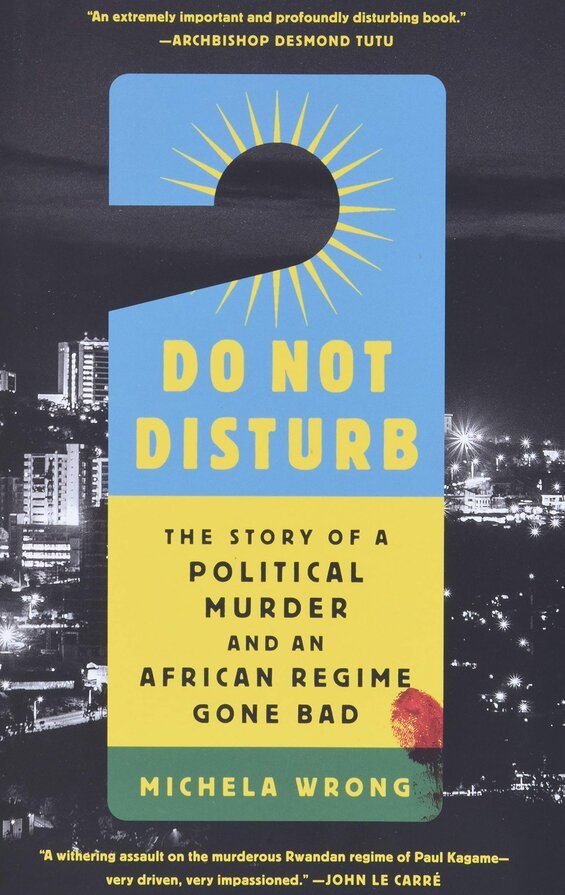

Do Not Disturb: The Story of a Political Murder and an African Regime Gone Bad by Michela Wrong (2021) 464 pages ★★★★★

A tale of three men, revolutionaries all

Do Not Disturb is framed as an inquiry into the murder of a high-level refugee from Rwanda in a Johannesburg hotel room in 2013. The book starts with a detailed account of the murder—an assassination, really—and closes with news of the much-delayed inquest in South Africa more than five years later. In between these bookends, Wrong relates the complex, three-decade history of the region that led up to the genocide. She shows how the story involves not just tiny Rwanda and its 12 million people but all the nearby nations as well, including Uganda, Burundi, Kenya, Tanzania, and what is today called the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Together, the five countries house a population approaching that of the United States.

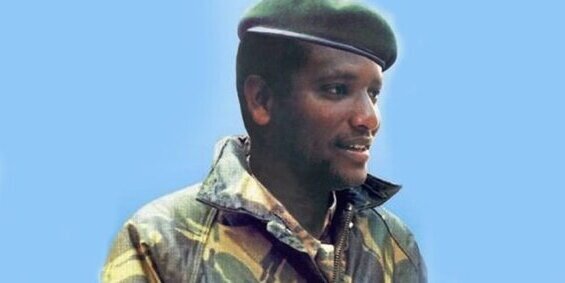

But, properly speaking, Do Not Disturb is a story of three men who were brothers-in-arms in the Uganda-based force that overthrew the génocidaire regime in Kigali. Paul Kagame (1957-), President of Rwanda since 2000. Patrick Karegewa (1960-2013), Rwanda’s long-time chief of intelligence and Kagame’s aide-turned-victim. And Fred Rwigyema (1957-90), the charismatic and much-loved leader of the revolutionary army who might well have led Rwanda had he survived the fighting.

Learning the rules for revolution in Uganda

Kagame, Karegewa, and Rwingyema were all members of the Tutsi ethnic community. Like so many others, they lived not in Rwanda but in neighboring Uganda. Karegewa even considered himself Ugandan, as his family had lived in the country for generations. As young men, they were all engaged in the brutal revolutionary movement that overthrew, first, the homicidal buffoon Idi Amin (1925-2003), and then his equally tyrannical successor, Milton Obote (1925-2005). The three all played roles in installing as Uganda’s president Yoweri Museveni in 1986, who remains in office to this day. Later, they came together again to mount an invasion of Rwanda, to overthrow the Hutu regime led by Juvénal Habiyarimana (1937-94). It was Habiyarimana whose death in a plane crash is generally credited with triggering the genocide.

A complex tale boiled down to essentials

As Michela Wrong tells it, this story is complex, full of twists, turns, and backtracks. But it’s essentially a simple tale. The three stars of the story—Kagame, Karegewa, and Rwingyema—collaborated uneasily in a revolutionary alliance for several years in Uganda before the 1990 invasion of their homeland.

The inspirational leader: Fred Rwingyema

The popular and compassionate Fred Rwingyema stood head and shoulders above the others. He was widely regarded as the man to replace Habiyarimana at the helm of Rwanda’s government once the Hutu regime fell.

The cheerful spy: Patrick Karegewa

Patrick Karegewa, who was close to the Ugandan revolutionary leader they all had followed, rose quickly in the independence movement, playing a leading role in securing resources from neighboring governments. With a cheerful, outgoing personality, Karegewa was, like Ryingyema, popular among the troops. He was the movement’s chief diplomat.

The control freak: President Paul Kagame

By contrast, Paul Kagame was unpopular and even despised by many who served with him. He was a dour and vindictive man known by his nickname “Pilato” (Pontius Pilate) for his demonstrated willingness to condemn colleagues to death for minor infractions. Wrong characterizes him as “the ultimate control freak.” Yet after Rwingyema died on the second day of the invasion of Rwanda in 1990, it was Kagame who took the helm of the movement and then the nation. Karegewa was among his aides as chief of external intelligence.

Controversy surrounds Fred Ryingyema’s death. He may have been felled by a stray bullet in battle with French soldiers who supported the Hutu regime—or at the hands of a jealous colleague in the revolutionary army. But there is no longer any mystery about Patrick Karegewa’s death. He was murdered by thugs in South Africa hired by Paul Kagame. He was one of many high-level Rwandan refugees and exiles killed for their refusal to remain complicit in the President’s crimes. And, as MIchela Wrong reveals about bringing this truth to light, “I’ve written books before that annoyed ruling regimes, but have never felt quite so personally at risk.”

Where is Rwanda?

Africa is vast. It’s nearly three times the size of the United States and houses a population topping one billion. So, tiny, landlocked Rwanda is easy to overlook on a map. You might imagine it as a dependency of its massive neighbor to the west, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) with its population of 92 million. Yet, as Michela Wrong shows, in some ways the opposite is the case. For many years, in fact, Rwanda has been the dominant force in much of the eastern DRC. And the Kagame regime was instrumental in deposing the dictatorship of Mobutu Sese Seko (1930-97), the DRC’s tyrannical, long-serving president. Rwanda’s population of just 12 million and its President Paul Kagame exert influence far out of proportion to their number.

So, why does Rwanda remain the poster child of African progress?

Why, then, if all this is true—and I am convinced it is, after independently checking parts of this report—does the international community continue to shovel resources into Rwanda? (Just for the record, here’s Michela Wrong noting one source of confirmation: “Google ‘YouTube,’ ‘Assassination,’ ‘General,’ and ‘Kayumba,’ and you can listen to Kagame’s henchmen at their sinister work, with subtitles in English and French helpfully provided.”) The author’s explanation emerges from her narrative. There seem to be four reasons:

1. Public relations

The public relations campaign President Paul Kagame’s minions have had underway since the beginning is singularly effective. It takes a lot of digging to turn up the truth about conditions in Rwanda and the history of the men at the country’s helm. And, as Wrong notes, “the storyteller’s need to identify Good Guys and Bad Guys, culprit and victims, makes fools of us all.”

2. Economics

In some cases, particularly those involving other African regimes, lucrative trade relations and other benefits have helped suppress any tendencies to express displeasure with the Kagame government.

3. A powerful army

The fact that Rwanda has, as Wrong notes, the most powerful army in Africa plays a role, too. Its frequent contributions to international peacekeeping forces make it possible for other nations to avoid participating in dangerous missions organized by the Organisation of African Unity or the UN.

4. Realpolitik

But, in the final analysis, realpolitik reigns here. Diplomats, aid officials, and philanthropists ignore the “human rights violations”—in reality, government-sanctioned murder—because they have higher priorities. Kagame paints a pretty picture of “progress” that looks good in their reports, and the doctored statistics are impressive. But the reality that emerges from Wrong’s account is that the Tutsi forces under President Paul Kagame’s leadership have murdered nearly as many people as perished in the genocide. The examples she cites from independent studies add up to about 700,000 dead. Some 800,000 to one million people died in the genocide.

As Wrong concludes, “Having broadly decided at one point that Kagame and the RPF were ‘the Good Guys’ in Rwanda, ‘Good Guys’ who had stopped what was self-evidently ‘A Very Bad Thing,’ many an academic, diplomat, development official, and businessman would cling with a sloth’s viselike grip to that view, pretty much irrespective of events on the ground or any suggestion that the RPF had, in fact, played a part in bringing that Very Bad Thing about.”

It’s a profoundly sad story.

About the author

Michela Wrong (1961-) spent six years covering events in Africa for Reuters, the BBC, and the Financial Times. She is the author of four nonfiction books about Africa and a legal thriller. Wrong lives in London, where she frequently is interviewed on the BBC, Al Jazeera and Reuters.

For more reading

Before I began writing these reviews, I read an earlier book by Michela Wrong, It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistle-Blower. It’s excellent.

You might also enjoy:

- 20 top books about Africa, including both fiction and nonfiction

- Third World poverty and economic development: a reading list

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, by Gregory Clark (Why is the Global North so much richer than the South?)

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.