Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

Every country has its foundation myth, and the United States no less than any other. Here, settlers fleeing religious persecution and poverty in Europe flooded our shores. They founded thriving colonies on the Eastern seaboard dedicated to freedom. After gaining their independence, they drove relentlessly across the continent “from sea to shining sea.” There were people already living on the land, of course. But they supported themselves mostly by hunting, living lives little changed from that of the hunter-gatherers of ancient times. Their resistance faded in the face of overwhelming odds. They couldn’t overcome the force of the country’s “Manifest Destiny.” Yet this myth is wrong in almost every respect. In An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, scholar Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz refutes it with eye-opening detail.

The story begins with first contact

According to the conventional wisdom, infectious disease killed as much as 90 percent of the people who lived in the Americas. But in fact disease was only partly responsible, as Dunbar-Ortiz makes clear. In North as well as South America, the colonists’ determination to eliminate the people in their way accounted for nearly as many deaths. Admittedly, they didn’t do all the killing themselves. They had adopted the practice of “pitting one Indigenous nation against another or factions within nations.” And that proved effective in both North and South America.

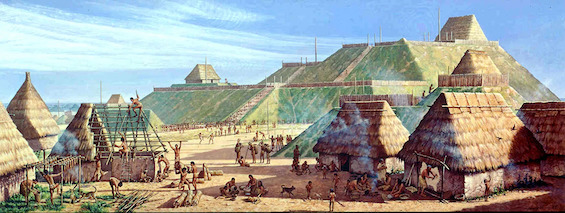

The numbers were large. “The total population of the hemisphere was about one hundred million at the end of the fifteenth century, with about two-fifths in North America, including Mexico,” writes Dunbar-Ortiz. “Central Mexico alone supported some thirty million people. At the same time, the population of Europe as far east as the Ural Mountains was around fifty million.” England housed 2.1 million at the time, Spain about eight million. By contrast, the land now within the borders of the United States contained an estimated fifteen million people.

It was, indeed, guns, germs, and steel that did the deed

And, no, it was not disease alone that reduced the indigenous population. To crib from Jared Diamond, it was guns, germs, and steel—plus the colonists’ unrestrained use of violence. Exterminating Native Americans became official government policy, and it rose to become the central mission of the American military. And this pattern, set at the outset, repeated itself for four centuries. The killing lasted until the “Indian Wars” came to a close on the cusp of the twentieth century.

But the pattern of US militarism had been set. And today American soldiers, sailors, and special operators continue to operate out of more than 1,000 overseas military bases. According to the Defense Manpower Data Center, “the military of the United States is deployed in most countries around the world, with between 160,000 to 170,000 of its active-duty personnel stationed outside the United States and its territories.” And, according to multiple sources, US special forces have operated in at least seventy countries in recent years. The number is probably larger.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014) 320 pages ★★★★★

A truly revisionist US history

Dunbar-Ortiz relates in sometimes excruciating detail the steady march of colonial intrusions into Indian land—and the seemingly endless story of the death that followed. Some of the most revered figures in the standard account of US history shamelessly, and often aggressively, supported the policy of extermination that the settlers followed on their way west and south. Not just Andrew Jackson, who was well known as an Indian fighter, but Thomas Jefferson. The author quotes him unapologetically urging settlers to slaughter any Indians who impeded their seizure of the land. And other iconic figures in our history—Daniel Boone and Kit Carson, for example—were Indian fighters who personally murdered uncounted numbers of Native Americans. You can’t read this book and continue to look on our history in the same way.

This account requires a larger context

Rather than starting with the landing of the Pilgrims, as the US foundation myth would have it, Dunbar-Ortiz describes the earliest European forays into the land now called the United States. Spanish settlements in Florida and the Southwest were thriving long before the British reached our shores. But unlike the British, they tended to coexist with the Native Americans they encountered, at least at first. By contrast, the British practiced settler colonialism. And, as Dunbar-Ortiz notes, “Settler colonialism, as an institution or system, requires violence or the threat of violence to attain its goals.” Ultimately, “The objective of US colonialist authorities was to terminate [the] existence [of Native Americans] as peoples—not as random individuals. This is the very definition of modern genocide.” And genocide it certainly was.

Of the fifteen million people who lived within our current borders when the English arrived in present-day Massachusetts and Virginia early in the seventeenth century, few remained by 1900. According to official figures, “The 1900 Census enumerated Indians living in the general population and on reservations. In that year, the American Indian population totaled 237,196.” Genocide, indeed.

Native Americans today

Today, Native Americans are divided among “more than five hundred federally recognized Indigenous communities and nations, comprising nearly three million people in the United States. These are the descendants of the fifteen million original inhabitants of the land, the majority of whom were farmers who lived in towns.”

The United States Census recognizes a larger group than do Native American scholars—”around 8.75 million people who identify at least partially as American Indian or Alaska Native live in the U.S.” No doubt, they can be found in every state, involved in every every industry and every profession. Just “13 percent [or about 1.1 million] live on reservations or other trust lands.”

But those lands leave a large footprint. As Dunbar-Ortiz reports, “The Diné (Navajo) Nation has the largest contemporary contiguous land base among Native nations: nearly sixteen million acres, or nearly twenty-five thousand square miles, the size of West Virginia. Each of twelve other reservations is larger than Rhode Island . . . and each of nine other reservations is larger than Delaware.” Yet all together these lands constitute less than three percent of the territory Indians and Native Alaskans called home when European settlers arrived five centuries ago.

About the author

According to her bio on the Beacon Press website, “Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, a New York Times best-selling author, grew up in rural Oklahoma in a tenant farming family. She has been active in the international Indigenous movement for more than four decades and is known for her lifelong commitment to national and international social justice issues. Dunbar-Ortiz is the winner of the 2017 Lannan Cultural Freedom Prize, and is the author or editor of many books, including An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, a recipient of the 2015 American Book Award.”

Wikipedia lists fourteen titles by Dunbar-Ortiz and notes that she was born in San Antonio, Texas, in 1938. She holds a BA from San Francisco State University, an MFA in creative writing from Mills College, and a PhD in History from the University of California, Los Angeles. She also received a Diplôme of the International Law of Human Rights at the International Institute of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France.

For related reading

This is one of the Top 20 popular books for understanding American history and one of the top 10 nonfiction books that changed my thinking.

For a similarly revisionist approach to the early history of the Americans, see two of Charles C. Mann’s excellent books:

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus Astonishing new evidence about the Americas before 1492)

- 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (After the Columbian Exchange, nothing was ever the same)

Two other superb recent books confirm Dunbar-Ortiz’s account of US colonialist history:

- How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr (A supremely entertaining history of American empire)

- The United States of War: A Global History of America’s Endless Conflicts, from Columbus to the Islamic State by David Vine (A powerful indictment of America’s permanent war)

You might also care to check out:

- Good books about racism

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.