In the previous entries in Ellis Peters’ Cadfael Chronicles, much of the focus lies on the contest between King Stephen (1096-1154) and his cousin Empress Maud (1102-67) over the English crown. The warring cousins crowd the background. But the seventh book, The Sanctuary Sparrow, resembles a cozy mystery confined to a small community and oblivious to outside influence. A young traveling minstrel is accused of murder and theft in the town of Shrewsbury, both capital offenses in 12th-century England.

The story is set in the year 1140. Brother Cadfael, the shrewd amateur detective who is the protagonist of the series, has his doubts from the first. Resisting pressure both from the town and his superior, Prior Robert, he doggedly pursues a series of small clues to uncover the truth. And that truth is no less than explosive when it finally emerges.

Unfamiliar language that conveys the pace of the times

When reading the Cadfael Chronicles, what’s most likely to jump out at you is the archaic syntax and sometimes unfamiliar language. Peters doesn’t, and couldn’t, accurately reproduce the language actually spoken in southwestern England in those years. It wasn’t English. Instead, it was a precursor known as Middle English, which we today can’t read without intensive study and couldn’t possibly speak. We can’t listen to those who did. But the effect the author creates suggests the pace and temper of the times.

The Sanctuary Sparrow (Cadfael #7 of 20) by Ellis Peters (1983) 289 pages ★★★★☆

When French invaded the Old English language

Keep in mind that the setting of this novel was in the mid-12th century, just decades after the Norman Invasion of 1066. The French rule England. King Stephen is also the Duke of Normandy. Maud, or Matilda, was also the Holy Roman Empress. With the French in command, the Saxon inhabitants of the country had become second-class citizens. And their language was fast evolving as terms from the Continent continued to gain traction in everyday life.

To read The Sanctuary Sparrow closely, it’s best either to view it online (with direct access to a historical dictionary and Wikipedia) or have at hand an edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. Also useful is A Glossary of Medieval Terms used in the series. Otherwise, you may well stumble over such words as rebec (a bowed stringed instrument), burgage (a rental property in a town owned by a lord), brychans (a blanket made of homespun wool), and orts (a scrap of food from a meal). Reading this novel, and using one of these sources, will persuade you just how unfamiliar was the language in 12th-century England.

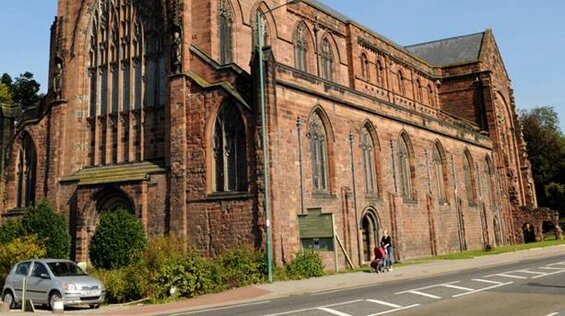

A cozy mystery in a familiar setting

“A poor vagrant jongleur” named Liliwin has been hired to entertain at the wedding of the goldsmith’s son, Daniel. Late in the celebration, Daniel’s drunken friends knock him over. In falling, the minstrel breaks a valuable vase belonging to the goldsmith’s notoriously intemperate mother. She forces him to leave with only a fraction of his pay. Soon afterwards, Liliwin shows up panting at Shrewsbury Abbey, pursued by a mob led by Daniel. They demand his release to them so he can pay for his crime. He has murdered the goldsmith and stolen his accumulated wealth, they insist. Though the language is unfamiliar, their fury comes through clearly. But Daniel has gained sanctuary for forty days in the monastery, and Abbot Radulfus forbids them to touch him on pain of god’s retribution. The Abbot calls on Brother Cadfael to take charge of the unfortunate lad.

It soon develops that it seems impossible for Liliwin to have committed the crime. And, in fact, the goldsmith was never murdered. Someone struck him over the head, and he remains groggy and uncommunicative for days. But he lives. Liliwin might hang, anyway, for theft is also a hanging offense. But Cadfael has gotten the scent of a crime that can only be explained if someone else was the culprit. Together with the sheriff’s trusted deputy, Hugh Beringar, Cadfael sets out on an investigation in hopes to finding the true offender before the forty days are up.

About the author

Ellis Peters (1913-85) was the best-known of several pen-names used by Edith Pargeter, an English author who wrote scores of novels and short stories, mostly historical fiction, as well as nonfiction, primarily history. She also became well known for her translations of works from Czech, a language she learned after a visit to the country in 1947. Her Welsh ancestry is reflected in the character of Brother Cadfael as well as many of her other works. Self-taught, she never attended university.

For more reading

I’ve reviewed all six previous novels of the Cadfael Chronicles. You can find them by typing the name Cadfael in the search box in the upper right-hand corner of the Home Page.

You might also enjoy my posts:

- Top 10 mystery and thriller series

- 20 excellent standalone mysteries and thrillers

- 5 top novels about private detectives

- 30 outstanding detective series from around the world

For an abundance of great mystery stories, go to Top 20 suspenseful detective novels. And if you’re looking for exciting historical novels, check out Top 10 historical mysteries and thrillers reviewed here.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.