In an even reasonably rational world, In Their Own Hands would serve as the Bible for development professionals and the basic textbook for students, philanthropists, faith-based activists, and business executives who aspire to improve the lives of poor people. Though this book advocates a particular methodology to promote financial inclusion, it’s the best overall introduction I’ve ever read to working with poor people in the Global South. If you have any interest in this topic, whatever your background or perspective, you owe it to yourself to read this brutally honest book.

In Their Own Hands represents the distilled wisdom Jeffrey Ashe has acquired over half a century of work with poor people across the globe. Ashe’s experience in fighting poverty began in his mid-twenties as a Peace Corps Volunteer in rural Ecuador and has continued seamlessly through the ensuing decades. During most of that time, he was one of the world’s leading practitioners of microfinance, with a career that began working for Accion International in Latin America several years before Muhammad Yunus’ rediscovery of the concept in Bangladesh. Then one fateful evening thirteen years ago at Brandeis University, where Ashe is now a faculty member, he attended a lecture by a woman named Marcia Odell, director of the Women’s Empowerment Program at Pact, who had introduced a novel approach to financial inclusion in rural Nepal.

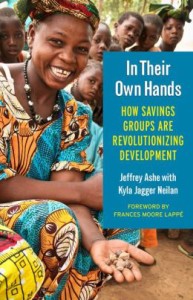

In Their Own Hands: How Savings Groups Are Revolutionizing Development by Jeffrey Ashe with Kyla Jagger Neilan ★★★★★

The method she described, village savings groups, had originally been developed by CARE in 1971 in Niger, but it was Odell’s presentation that brought it to the center of Ashe’s attention. Savings groups struck him as a brilliant answer to the shortcomings he had witnessed in microfinance. Ashe finagled a contract to evaluate her program in the field, and soon afterwards he began designing a similar effort to introduce into the desperately poor West African nation of Mali.

Now, little more than a decade later, due in no small part to Ashe’s influence, “there are savings groups with ten million members in at least a hundred thousand villages in sixty-five countries.” The leading NGOs that have spearheaded the effort — Oxfam America, Freedom from Hunger, CARE, Catholic Relief Services, Plan International, the Aga Khan Foundation, and Pact — have recently dedicated themselves to a collaborative effort to reach fifty million people by 2020.

The key to work with poor people through savings groups

The key to understanding savings groups is that they do NOT represent a method to end poverty, as some of their more extravagant boosters have suggested. As Ashe explains, “Joining a savings group will not lift many out of poverty — no development initiative can deliver on that promise — but regular savings and a reserve of cash can help reduce life’s uncertainties.” To those of us who enjoy privileged lives in the Global North, that benefit may seem trivial. However, to the global poor, it can seem a lifesaver — which is why savings groups have spread so readily and persisted for so long in so many countries.

“In Mali,” Ashe notes, “despite a coup, an insurgency in the north, a severe drought, an influx of refugees, skyrocketing food prices, limited opportunities for work outside the village, and faltering institutions, few Saving for Change groups have disbanded while many new groups have been trained by volunteers. Similarly, groups in Zimbabwe survived hyper-inflation, and groups in Nepal thrived after the withdrawal of outside support and a Maoist takeover of the region.”

Nine principles for success

Ashe cites “nine principles needed for success” that can be applied to any economic development effort, not just village savings groups:

- Start small to learn, but plan for scale.

- Simple is better than complex.

- Build on what is already in place and already widely understood.

- Design for change that persists long after outside agents leave and that spreads from village to village without outside staff.

- Keep costs low.

- Give nothing away.

- Insist on local control.

- Establish high performance standards and insist on meeting them.

- Build learning and innovation into program design.

Somebody should carve these precepts onto thousands of granite tablets and erect one set above the doorway of every NGO, every development agency, every university, every multilateral institution, and every business that seeks to improve the lot of poor people around the world.

For the record, Jeff Ashe and I have been friends for nearly fifty years, since we met in a Philadelphia hotel room for Peace Corps orientation. We worked together closely in Peace Corps training in Puerto Rico and, after a year in-country in Ecuador, we teamed up with several fellow Volunteers on a project Jeff inspired to help implement that country’s new agrarian reform law. There are few people anywhere in the world for whom I have more respect than Jeff — or longer experience to justify it.

For further reading

See also 20 top books about Africa, including both fiction and nonfiction.

For books on closely related topics, see:

- Narrowing global inequities: a reading list

- Third World poverty and economic development: a reading list

- The top 10 books on the economics of poverty

- A resource list on social enterprise

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.