Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

Far too few Americans acknowledge the ugliest aspects of our history. Slavery and Jim Crow. The genocide of Native Americans. The “Yellow Peril.” The U.S. conquest of Cuba and the Philippines. Typically, our history books treat these events as isolated and disconnected. Dig a little deeper into the sources, though, and it becomes unmistakably clear that unapologetic racism dominated Americans’ thinking for at least the first century and a half of our history as an independent nation. And it came to fruition at the turn of the 20th century when Teddy Roosevelt and racism dominated US foreign policy.

Teddy Roosevelt and racism

It was racism that account for all those ugly chapters in the conduct of American foreign policy and, more broadly, throughout U.S. history. Not polite racism, but one powered by anger and manifested as a theory of Aryan superiority indistinguishable from the beliefs that drove Adolf Hitler. For insight into this sad reality, James Bradley’s eye-opening treatment of Teddy Roosevelt’s foreign policy, The Imperial Cruise, is a superb beginning.

The Imperial Cruise: A Secret History of Empire and War by James Bradley (2009) 401 pages ★★★★☆

Racism was rampant in turn-of-the-century America

Racist attitudes were so prevalent and unchallenged in the U.S. at the turn of the 20th Century that the president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science—the founder of anthropology in the U.S.—could observe, “The Aryan family represents the central stream of progress, because it produced the highest type of mankind, and because it has proved its intrinsic superiority by gradually assuming control of the earth.” In hindsight, then, it should be no surprise that such celebrated figures as Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and his successor, William Howard Taft, would speak openly about America’s “destiny” to dominate Asia and the Pacific, imposing the benefits of Aryan civilization on the “Pacific niggers” (their term for Filipinos) and “Chinks.”

This is the persistent theme of best-selling author James Bradley’s portrayal of Roosevelt and Taft in The Imperial Cruise. Teddy Roosevelt and racism were inextricably linked.

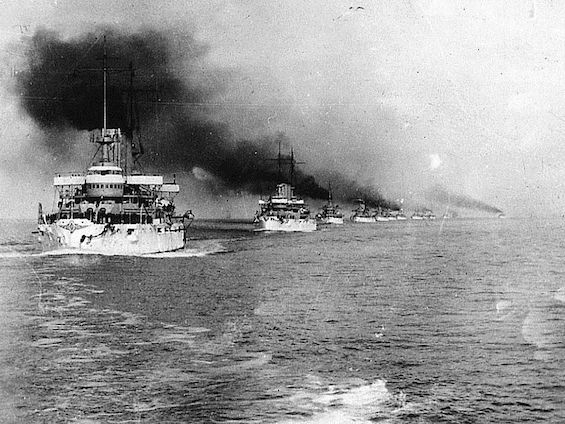

A grand cruise to conquer the Pacific

After returning to the U.S. from the Philippines, where he directed the brutal American occupation of the islands, Taft quickly became Roosevelt’s confidante and “assistant president” though nominally serving as Secretary of War. When Roosevelt resolved in 1905 to extend the U.S. empire throughout Asia, he sent Taft on a secret diplomatic mission to Japan, a mission cloaked in a grand cruise of the Great White Fleet with a huge party of Senators and Congressmen and the President’s own 21-year-old daughter, Alice.

Alice’s antics—she was a “wild child” in the buttoned-down culture of the times—drew headlines and enormous crowds of admirers. Meanwhile, Taft shared a secret plan with the Japanese “whereby Roosevelt would grant them a protectorate in Korea in exchange for Japan’s assisting with the American penetration of Asia.” The ecstatic Japanese quickly accepted the deal, which to them was all about their existing occupation of Korea. They had no intention whatsoever of letting the U.S. horn in on their efforts to absorb China.

Teddy Roosevelt betrayed the Japanese

The deal with Japan that Taft brought to closure was secret not just from the public but from Roosevelt’s own Secretary of State, not to mention Congress. It came to light only two decades later when the secret papers recording the history of the cruise and the diplomatic exchanges surrounding it came to light. Roosevelt knew that neither the State Department nor Congress would approve anything of the sort. As Bradley notes, “The president of the United States had skirted the Constitution and negotiated a side deal with the Japanese at the same time he was posing as an honest broker between Japan and Russia at the Portsmouth peace talks” held to end the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5. But, since all this was secret, the jury that awarded Roosevelt the Nobel Prize for Peace because of the pact was entirely ignorant of his true role in the negotiations.

Ironically, Roosevelt managed to spark four decades of hatred toward the U.S. by giving the Japanese the impression that he would steer the peace talks as they wished—and then delivering an agreement that fell so far short of what they’d expected that the Japanese public felt betrayed. (Bradley attributes the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor from this perceived betrayal, which seems far-fetched.)

TR was deeply flawed by racism

Historians and biographers typically portray President Theodore Roosevelt as a heroic figure, a man of surpassing intelligence and a profound commitment to reform. In The Imperial Cruise, Bradley presents a starkly revisionist view, relating Roosevelt’s deep-seated racism, his blatant, life-long self-promotion, his duplicitous and often ill-conceived foreign policy, and his consummate narcissism. Though Bradley’s logic falters on occasion, his portrait of Roosevelt is all too credible, the man’s Pulitzer-Prize-winning biographers notwithstanding.

Consider, for example, Roosevelt’s own words from his 1896 best-selling book, The Winning of the West: “Many good persons seem prone to speak of all wars of conquest as necessarily evil. This is, of course, a shortsighted view. In its after effects a conquest may be fraught either with evil or with good for mankind, according to the comparative worth of the conquering and conquered peoples . . . The world would have halted had it not been for the Teutonic conquests in alient lands; but the victories of Moslem over Christian have always proved a curse in the end.”

About the author

James Bradley has written extensively about World War II in the Pacific in three nonfiction books. His father, John Bradley, was one of the US Marines who first raised the flag on Iwo Jima. But he was not in Joe Rosenthal’s iconic photo of the flag-raising, which was later posed by the photographer and included other Marines raising a much larger flag. Bradley’s first book, Flags of Our Fathers, was about his father’s role in the war and appeared on the New York Times bestseller list for 46 weeks. Bradley was born in 1954 in a small Wisconsin town.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed The China Mirage: The Hidden History of American Disaster in Asia by James Bradley (“Who lost China?” Nobody.).

I’ve reviewed two other good books on related subjects:

- The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of the American Empire by Stephen Kinzer (The racist origins of the American empire)

- How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States by Daniel Immerwahr (A supremely entertaining history of American empire)

And for an entertaining murder mystery during the time when TR was NYPD Police Commissioner, see Hot Time by W. H. Flint (Teddy Roosevelt at the NYPD during the 1896 election).

This is one of the books I’ve included in my post, Gaining a global perspective on the world around us.

You might also enjoy:

- 13 good recent books about American foreign policy

- Good books about racism reviewed on this site

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.