Some of the greatest works of literature in the 20th century addressed the theme of colonialism. Things Fall Apart by China Achebe. Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The Wretched of the Earth by Franz Fanon. And E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India. There are many more. The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver isn’t routinely listed among them. But it should be. Although much of the action takes place after the Belgians have granted independence to the country, the book is all about the terrible, lingering effects of colonialism in the Congo. Written in gorgeous prose and firmly rooted in the tragic events of the early 1960s, the novel stands in testimony to the price paid by millions for the greed and racism of the white Europeans who plundered their land.

Estimated reading time: 8 minutes

Preaching amid the clamor for independence

The story begins as Baptist missionary Nathan Price, his wife, Orleanna, and their four daughters settle in a Congolese village in 1959. Price has come to save souls, but the people of Kilanga alternately find his preaching to be either insulting or impossible to understand. They have their own religion, after all. In rotating chapters, the five women of the family narrate the action that unfolds over the ensuing years. As they struggle to survive in the unfamiliar and dangerous environment of tropical Africa, events quickly spin out of control in the huge, wealthy country around them.

The end of colonialism in the Congo . . . or is it?

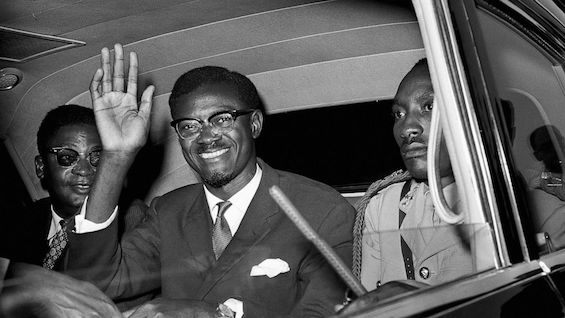

The growing clamor for independence forces Belgian authorities to set a timetable for their departure, then to accelerate it as violence spreads. A charismatic young postal worker named Patrice Lumumba emerges as the popular choice to lead the new country. He is overwhelmingly elected, only to be deposed after two months in office and then murdered by the CIA and the Belgians. The outsiders are desperate to hold onto their control of the Congo’s mineral wealth. In the cause of “anti-communism,” they install a corrupt, homicidal army officer named Joseph Mobutu (later, Mobutu Sese Seko) in Lumumba’s place. And Mobutu sets out on what ultimately becomes a 32-year record of terror, looting, and repression that keeps the country’s millions of people destitute and yearning for change.

The Poisonwood Bible by Barbara Kingsolver (1998) 579 pages ★★★★★

Principal characters: the family

The five members of the Price family are at the center of the action:

Nathan Price

Rev. Nathan Price is a World War II veteran who was the sole survivor of his company’s tragic experience on the Bataan Death March, and he has never been the same since. He is nominally a Baptist preacher but ignores direction from his superiors in the denomination. He has dragged his family to the Congo against orders to stay. Once in the village, he quickly alienates the local folk by denouncing their customs and beliefs. And he is clueless about the legacy of colonialism in the Congo. Nathan is equally dismissive of the women in his family, forever upbraiding them for imagined sins and transgressions against the word of God, as he sees it.

Orleanna Price

Mrs. Price is “Southern Baptist by marriage, mother of children living and dead” by the conclusion of the book. It’s obvious to her and her older daughters that she made a huge mistake in marrying Nathan, but throughout their year in Kilanga, as their fortunes steadily decline, she cannot find the will or the reason to leave him. Orleanna is clearly both more level-headed and intelligent than her husband, and, unlike him, regards the villagers as people just like them despite their different upbringing and circumstances.

Rachel Price

Rachel is the princess of the family. The eldest of four daughters, she is by all accounts beautiful, a slender young woman at 16 or 17 with long, almost white blonde hair. Profoundly self-involved, she looks down on her sisters, all of whom are far more intelligent. Rachel cares only about preserving her looks and avoiding contact with the people of Kilanga as much as possible. Like her father, she displays no interest in understanding the local customs and beliefs. She personifies the disdainful attitude so typical among European colonizers. For her, colonialism in the Congo was merely an expression of superior people bringing gifts to their African inferiors.

Leah and Ada Price

The twins have but one thing in common: both are intellectually gifted—brilliant, in a word. They’re only two years younger than Rachel, but both are far more aware of the circumstances into which they’ve been plunged by their thoughtless father. Still, Leah is devoted to him, following him everywhere she can and rejoicing in the Gospel as he teaches it. Adah is more critical. She is disabled, leaning to one side and limping because her brain was deprived of oxygen in the womb. But that accident of birth also left her with unique mathematical and verbal gifts. However, throughout the family’s stay in Kilanga, she remains mute, as she has since birth, communicating only through gestures and facial expressions.

Ruth May Price

Ruth May is the baby of the family, nearly a decade younger than the twins. She is a bright and adventurous child, forever wandering off into the forest and playing with the children of the village, who flock to her side.

Principal characters: the local people

A handful of villagers emerge as individuals in the story:

- Tata Undo is the chief of Kilanga. He develops a special interest in one of the Price girls, whom he would like to add to his houseful of wives. Others among the men of the village are Tata Zinsana, the “witchdoctor,” and Tata Boanda, a fisherman. Tata Zinsana is bitterly opposed to Nathan’s mission. Tata Boanda is supportive of the family.

- The notable women of the village include Mama Mwanza and Mama Nguza, who take pity on the Price women, and Mama Tataba, who works for the Prices “doing the same work she’d done for our “forerunner in the Kilanga Mission, Brother Fowles.”

Two other white people in the region who surface in the novel include:

- Eeben Axelroot, an avaricious bush pilot who will become a major factor in the Congo. He signs on as a contract killer for the CIA—for the money.

- Brother Fowles was Nathan Price’s predecessor as a missionary in Kilanga. Unlike Nathan, he adjusted to the local customs and gained a large following in the village.

The saga continues

Much of the text in The Poisonwood Bible traces the tragic experiences of the Price family in Kilanga from 1959 to 1961. Later chapters follow the four surviving women for decades after their hasty departure from the village. In her account of the women’s later experiences, Kingsolver skillfully traces the history of the Congo (later, under Mobutu, Zaire) as she follows them on their disparate paths. Some return to Georgia, others to new homes in Angola and the Republic of the Congo across the river from what has become the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The historical backdrop

Belgium was a latecomer to the Scramble for Africa. Then, as Wikipedia notes, “the 10 percent of Africa that was under formal European control in 1870 increased to almost 90 percent by 1914.” The famous explorers David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley, unable to secure support anywhere else, pioneered European penetration of the vast, uncharted region of the Congo with the patronage of King Leopold II of Belgium.

Despite pressure on all sides from British, French, and Portuguese, Leopold managed to exert control over 890,000 square miles in the region shortly after the turn of the 20th century. This was an expanse of land about 75 times the size of Belgium itself. He claimed the land not for his nation but for himself personally. And the regime he imposed on the hapless people of the area was brutal to an extreme, perhaps the most murderous example of colonial rule that history can offer. An estimated three million Congolese lost their lives, and millions more lost their hands to the merciless overseers on Leopold’s lucrative rubber plantations. The legacy of misrule in Congo’s past is the background to this moving novel.

About the author

Barbara Kingsolver was born in 1955 and raised in rural Kentucky. In early childhood, she lived briefly in what is today the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where her parents worked in public health (not a Christian mission!). She has written eight novels since 1988 as well as two volumes of essays, two of poetry, and three works of nonfiction. Kingsolver holds a BS degree in biology from DePaul University in Indiana and a Master’s in ecology and evolutionary biology from the University of Arizona.

For related reading

I’ve also reviewed three of the authors other novels:

- The Lacuna (Leon Trotsky, Diego Rivera, and the Red Scare)

- Flight Behavior (Barbara Kingsolver writes eloquently about climate change)

- Demon Copperhead (An engrossing novel of the drug epidemic)

You might also enjoy A Bend in the River by V. S. Naipaul (Nobel Prizewinner paints an unflattering picture of Africa) and 20 top books about Africa. For an insightful nonfiction account of the colonial regime in Congo, see King Leopold’s Ghost by Adam Hochschild.

And check out Top 10 great popular novels and 20 most enlightening historical novels.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.