Over the past decade, beginning with the police murders that triggered the Black Lives Matter movement, discussion of reparations for slavery has surfaced in public discourse across the United States. After all, some four million African-Americans were enslaved in 1860. And their descendants, the overwhelming majority of the forty-two million Black people in the USA today, live with that legacy. To many of us—a clear majority of African-Americans and more than a quarter of the US population as a whole—agree that that legacy affects Black lives a great deal today. Its central pillar—systemic and pervasive racism—has held back generations of African-Americans for four centuries. Many know now that reparations could begin to reduce the damage. But reparations are far from a new idea. They were a subject of debate in the nineteenth century even while slavery was still in force. And historian Caleb McDaniel’s masterful, Pulitzer-Prize-winning book, Sweet Taste of Liberty, brings that debate to light. It seems especially fitting to recall all this now during Black History Month.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

The extraordinary life of a freed slave

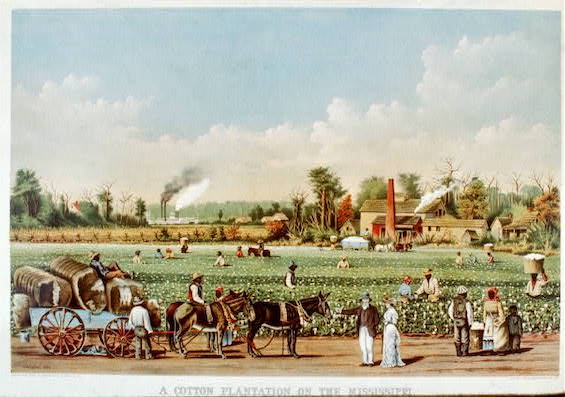

In Sweet Taste of Liberty, McDaniel relates the extraordinary story of Henrietta Wood (c. 1818-1912). Born into slavery in 1818 or 1820, she was freed in 1848 and experienced life as a free woman for five years in Cincinnati. Then the daughter of a former owner connived to take her back to Kentucky, which was then a slave state. There, a gang of slave traders kidnapped her. They sold her “down the river,” and Henrietta ended up on an industrial-scale cotton plantation near Natchez, Mississippi.

She labored in the fields for a time before the owner ordered her into his home, where she worked as a laundress, housekeeper, and nanny. When Federal troops menaced the city during the Civil War, the owner fled to Texas with hundreds of his slaves, including Henrietta. There, she remained in bondage until long after the war and emancipation. Eventually, however, Henrietta made her way back north. A friendly abolitionist attorney back in Cincinnati helped her file suit against the man who had orchestrated her kidnapping and sale. McDaniel tells the story of that lawsuit, which captured headlines all across the United States.

Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution in America by W. Caleb McDaniel (2019) 352 pages ★★★★★

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for History

The lawsuit that elevated discussion of reparations

McDaniel gives us convincing portraits of several key figures in his story. Henrietta, of course. The French immigrant, William Cirode, who owned her in Lexington and New Orleans before her emancipation. Gerard Brandon, owner of the Mississippi plantation. George B. Kinkead, the prominent antislavery attorney who arranged her lawsuit. But, most convincingly, Zebulon Ward, the sociopath who arranged for her kidnapping and sale. The author describes Ward’s long career as warden of the state penitentiaries in three states (Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas). In those hugely lucrative posts, he presided over a regime of terror and cruelty that established the character of the convict licensing system present in the South for decades thereafter.

However, Sweet Taste of Liberty is above all the story of the lawsuit that Henrietta waged for nine years in Federal court to secure compensation for her re-enslavement. It’s a stirring and ultimately inspiring tale. Against all odds, she won her case. But the compensation fell far short of the $20,000 she had demanded (roughly $700,000 today) for the kidnapping and sixteen years of slave labor. In 1879, the federal District Court in the Southern District of Ohio ordered Ward to pay her just $2,500 (the equivalent in 2023 of about $74,000 after inflation). Newspapers across the United States, which had been following the case closely since its inception, complained that the amount was far too low. And that recognition brought into greater prominence the public discussion of reparations that had surfaced from time to time in previous years.

Setting the precedent for reparations

“Before abolition,” McDaniel observes, “freedom suits in the slave states had sometimes included claims for monetary damages, but the amounts paid or even requested in such suits had never been as high as five figures. And although some abolitionists and radical Republicans had advocated reparations of some form to the enslaved, previous efforts had fallen short.” Still, in isolated cases, former slaves did win restitution in court. And the precedent was set.

“Enslaved people—women in particular— had always understood slavery as a crime that demanded reparation,” McDaniel writes. “Near the close of the American Revolution, for example, a manumitted woman named Belinda had successfully petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for a small pension paid out of the estate of her former owner on the grounds that his wealth had been partly ‘accumulated by her own industry,’ as the petition stated, and ‘augmented by her servitude.’ Now, seven decades later, many formerly enslaved people were arguing the same thing.”

In the commentary that swirled around the decision in Henrietta’s case against Zebulon Ward, the New York Times raised “some difficult questions about the nation’s ‘unsettled account’ with the formerly enslaved. As the Times noted, ‘former Confederates and Democrats could still be heard arguing, on occasion, that they were owed compensation for the loss of their slaves or forgiveness of their debts from the war. To them, the Times asked, what about compensation to ex-slaves?”

“Juneteenth,” explained

Many African-Americans, especially those whose roots lie in Texas, celebrate Juneteenth. The date, June 19, commemorates the freeing of slaves in Texas in 1865, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation. Although enslaved persons throughout the Confederacy had been “freed” in 1863, only the arrival of Union troops made the order a reality. And that didn’t happen in Texas until months after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Even so, slavery persisted in areas of the vast state distant from the major cities. And “as Wood later recalled in 1879,” McDaniel writes, “[Gerard Brandon] kept his slaves working on his rented plantation for three more years.”

Slavery was, indeed, the cause of the Civil War

To this day, many stubborn Southerners insist that slavery was not the cause that animated the Confederacy. McDaniel makes clear in passing that their objections are so much flimflammery. “By 1860,” he writes, the nearly four million people enslaved in the United States would be worth an estimated $3 billion to their owners, more than all the factories, railroads, and banking capital in the country combined. White fears over the threats to all that wealth would soon spark a civil war.” And a great many Southerners were well aware of that reality at the time. As the war wound on, complaints were heard among Confederate soldiers that the conflict was “a rich man’s war and a poor man’s fight.”

About the author

At Rice University in Houston, Texas, W. Caleb McDaniel focuses his research and teaching on the nineteenth century, the Civil War Era, and the struggle over slavery. Currently, he chairs the Department of History and serves as co-chair of the university’s Task Force on Slavery, Segregation, and Racial Injustice. McDaniel was born and raised in San Antonio. He received BA and MA degrees from Texas A&M University and a PhD from Johns Hopkins University.

For related reading

This is one of The 21 best books of 2023.

I’ve also reviewed four other excellent books that address the history of slavery:

- Horse by Geraldine Brooks (A novel about a famous racehorse sheds light on slavery)

- Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” by Zora Neale Hurston (The last living former slave tells his story)

- Washington Black by Esi Edugyan (A haunting story about slavery and science in the 19th century)

- Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert (Capitalism reexamined from an historical perspective)

You might also check out:

- Good books about racism

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- My 10 favorite books about business history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.