Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

We’ve been taught that the modern world dawned when Christopher Columbus arrived in the Caribbean in 1492 in search of a route to the riches of “India.” In fact, for centuries, historians have been telling us that everything changed because explorers from Spain and Portugal set out across the unknown reaches of the seas to establish new trade routes to what we know today as China, Indonesia, and India. Without question, the ensuing Columbian Exchange played a large role in setting off the Great Divergence between East and West. But in Born in Blackness, a compelling new revisionist history, Howard W. French persuasively offers an alternative explanation about the origin of the shift.

“The first impetus for the Age of Discovery,” he writes, “was not Europe’s yearning for ties with Asia, as so many of us have been taught in grade school, but rather its centuries-old desire to forge trading ties with legendarily rich Black societies hidden away somewhere in the heart of ‘darkest’ West Africa.”

The lust for gold ignited the slave trade

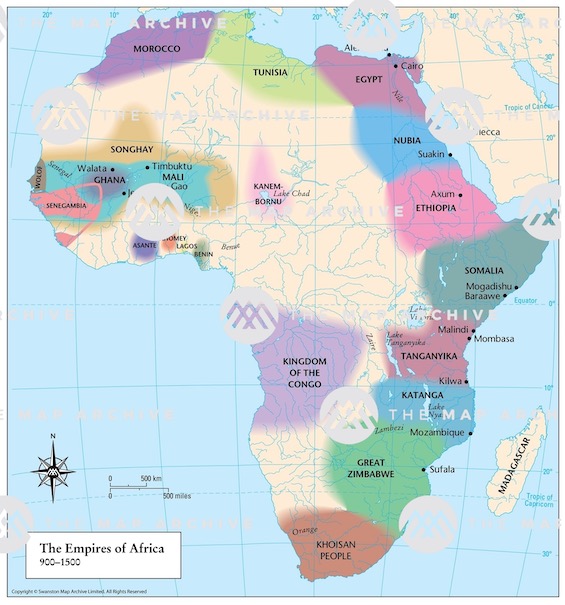

In the beginning, it was all about gold. Nearly 170 years before Columbus’ first voyage to the New World, the ruler of the fabulously wealthy Mali Empire set out eastward with a retinue of 60,000 men and women. Carrying as many as 18 tons of gold to distribute as gifts, Mansa Musa journeyed to the Middle East to prove he was the equal of the Islamic rulers of Egypt and the other Arab caliphates. Scholars in centuries to come have reckoned him the richest man in history. Word about Musa’s astonishing wealth eventually reached the nations of Europe, igniting their lust for gold.

“An abundance of modern scholarship,” French insists, “shows that more than any other cause or explanation it was the sensation stirred by news of Mansa Musa’s 1324 sojourn in Cairo and pilgrimage to Mecca, more than any of the more traditional theories, that set the creation of an Atlantic world into motion.” The agent of this change, in the 15th century, was Portugal. It was Portuguese ships sent down the west coast of Africa in search of gold that soon found a more lucrative endeavor in trading for slaves instead of the yellow metal. And the abundant wealth generated by four centuries of trade in African slaves built the empires of Portugal, Spain, France, the Netherlands, and England.

Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War by Howard W. French (2021) 528 pages ★★★★★

Five major takeaways

The principal thesis of Born in Blackness is that the slave trade that flourished from about 1450 to 1850, not the “discovery” of the Americas, was the engine of change. It lifted Europe from poverty, financed the rise of global trade, and powered the Industrial Revolution. But French offers an abundance of other insights into the history of the past 500 years. Of the many to be found in the pages of this remarkable book, I’ll convey five that stand out.

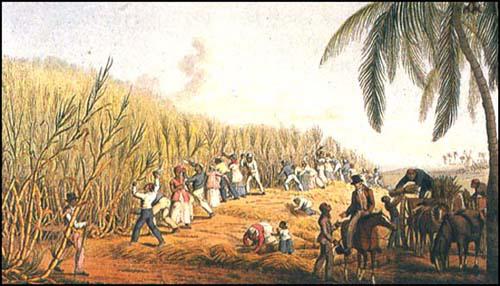

The sugar industry drove Europe into the modern era

Much is made of the role of cotton in sustaining the slave trade. But the cotton industry didn’t come into its own until the 19th century, driven by the unquenchable thirst for the fiber from the rapidly industrializing textile industry that mushroomed into existence in Britain. Two centuries earlier, sugar played a similar role. First on the Portuguese-owned island of São Tomé and later on the islands of the Caribbean and in Brazil, the Europeans (principally Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French) built slave plantations to grow sugar.

The profits were fabulous. And, as French notes, “the violently marshaled labor of Blacks led to much more lasting productive economic activity—with far more opportunities for what economists call virtuous feedback loops—than the mining that drove Spain’s acquisition of wealth from the New World ever would.” And those profits financed the establishment of colonies across the Atlantic and, later, the growth of industry in Western Europe that today we call the Industrial Revolution.

It’s difficult to grasp today just how large a role sugar—and the slaves who farmed it—played in the Atlantic economy. “By 1660 it is estimated that tiny Barbados’s sugar production alone was worth more than the combined exports of all of Spain’s New World colonies.” This included the prodigious output of silver from Spain’s silver mountain in Potosí, Bolivia, and its mines in northern Mexico. “And this was just for starters. From 1650 to 1800, as major new sugar islands came on line in the Caribbean, sugar consumption in Britain would increase 2500 percent, and over this time, the market value of sugar would consistently exceed the value of all other commodities combined.”

The 13 colonies were marginal to the British

“Specialists aside,” French writes, “few imagine that islands like Barbados and Jamaica were far more important in their day than were the English colonies that would become the United States.” The two islands produced substantially more wealth for Britain than all 13 colonies taken as whole. The riches that underwrote the expansion of the British Empire flowed not from North America but from the Caribbean—and it was wealth on a scale that few had dreamed possible. The North American colonies played only a peripheral role in this commerce—as merchants. The farmers, fishermen, and tradesmen centered on Boston, Philadelphia, and New York supplied food to the islands and clothed the slaves, themselves growing prosperous in the process.

From a broader perspective, the marginality of the North American colonies can be seen in the Europeans’ allocation of the slaves they captured in Africa. Forty-seven percent went to Brazil, and 42 percent to the islands of the Caribbean. Just 7 percent were sent to the 13 colonies. Take the island of Martinique, for example. As French reports, “Despite being less than one-fourth the size of Long Island, its sugar production drew more imports of slaves than the total volume of Africans trafficked to the United States throughout its history, including the colonial era.”

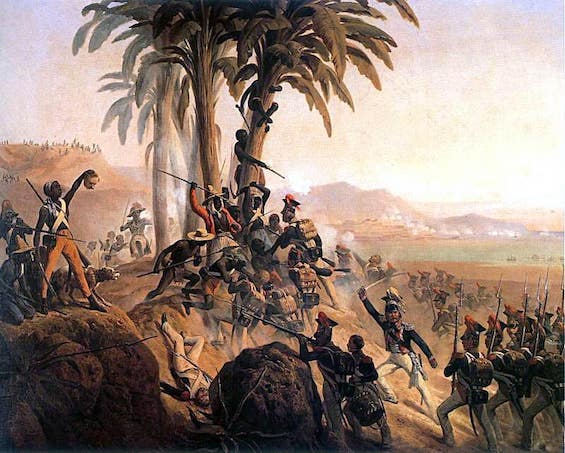

Haiti’s slave revolution helped build the United States

French recounts in sometimes numbing detail the history of slave revolts, making the case that resistance to enslavement among the African captives and their descendants was far more extensive than is generally understood. Over the years, although revolts were always successfully defeated, thousands of slaves did flee bondage. Throughout the New World, from Brazil to Mexico to the United States, these “maroons” formed independent, self-governing communities. But it wasn’t until the Haitian Revolution beginning in 1791 that a slave uprising succeeded. And that revolution shook the world.

In the 18th century, Haiti was the richest colony in history. And when its slave population successfully rebelled against the French and defeated huge armies sent by the French, British, and Spanish in the succeeding years, “Haiti rivaled the United States in terms of its influence on the world, notably in helping fulfill the most fundamental Enlightenment value of all, ending slavery.” And the impact on the size and shape of the United States was also profound.

For Napoleon Bonaparte, the deaths of thousands of troops in a futile effort to defeat the rebels and the loss of France’s most valuable colony were catastrophic. The loss forced Napoleon to abandon his hopes for empire on the North American mainland. When envoys from President Thomas Jefferson arrived in Paris to negotiate rights for US farmers and merchants to travel on the Mississippi, the French emperor astonished them by offering the entirety of Louisiana. The resulting $15 million Louisiana Purchase in 1803 nearly doubled the size of the United States.

The demographic impact of the slave trade in Africa was massive

“One sophisticated recent assessment of the continent’s demographics has suggested,” French writes, “that as a result of the slave trade of the modern era, by 1850, Africa’s population had been reduced to roughly half of what it would have been had there been no mass trafficking in humans.” An estimated 18.5 million Africans were trafficked—12.5 million to the New World and another 6 million to the Middle East or directly northward to Europe—but those numbers represent only a portion of the demographic damage.

“Establishing reliable numbers for the deaths that occurred during slaving-related warfare, capture, and especially the trek from the interior to the coast from slave-trading regions is probably an impossible task. Some historians have estimated, nonetheless, that as many Africans may have perished in these ways as survived the transatlantic passage.” And as a result, “some experts believe that . . . Africa’s population actually declined in absolute terms during the four centuries of the Atlantic trade.”

Why much of Africa today remains underdeveloped

The Scramble for Africa began following the Berlin Conference of 1884. At the time, “Europeans barely controlled 10 percent of the continent” despite five centuries of encroachment in search of gold and slaves. “By 1914 . . . Old Continent monarchs and other rulers held sway over 90 percent of Africa. The borders these European leaders agreed to among themselves remain the borders in force across most of the continent today.” And we see the results in the chronic African wars, coups, and dysfunctional governments even now in the 21st century.

The Scramble for Africa “left an enduringly debilitating legacy for the continent: a plethora of puny and scarcely functional states, with conflict among and between ethnic groups, and with some once coherent groups left pointlessly straddling borders and others with far less in common, just as illogically jumbled together in an artificial confection.” When observers of Africa debate the impact of colonialism, they often overlook this most obvious outcome of Europe’s disdain for the history, culture, and people of the continent.

About the author

For many years Howard W. French (1957-) worked for the New York Times as a foreign correspondent, reporting from China and from West and Central Africa and serving as bureau chief for the Caribbean and Central America. Later, he covered Japan and Korea as Tokyo Bureau Chief. Since 2008, French has been a professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is the author of four other books.

For related reading

This book is among The best nonfiction of 2022 and it’s one of the top 10 nonfiction books that changed my thinking.

Be sure to check out Empire of Cotton: A Global History by Sven Beckert (Capitalism reexamined from an historical perspective), which supports French’s thesis in broad outline. And you’ll find an excellent history of the abolition movement in Bury the Chains by Adam Hochschild.

You might also enjoy:

- 20 top books about Africa, including fiction and nonfiction

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Good books about racism reviewed on this site

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.