Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

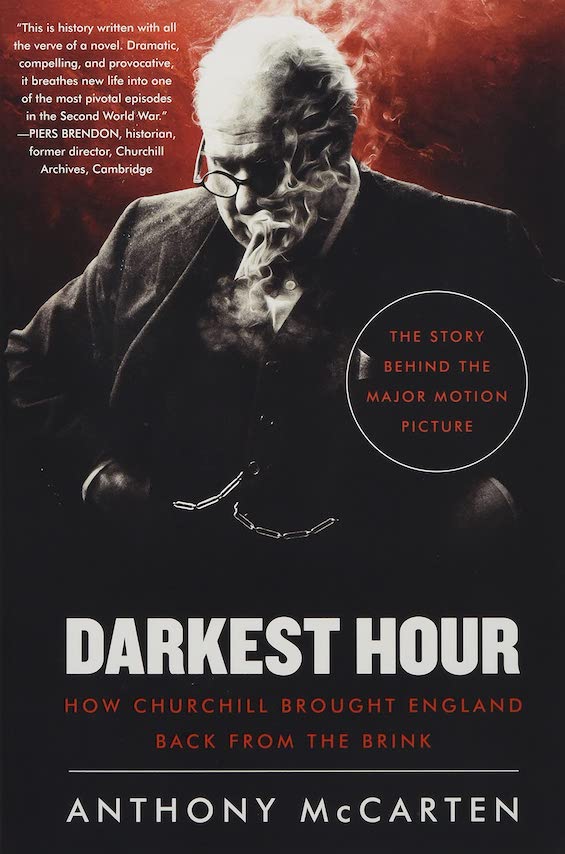

Most accounts of World War II convey the impression that Britain speedily turned to Winston Churchill as Prime Minister once Hitler’s stormtroopers proved the folly of Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement policy. Through his indomitable will and soaring rhetoric, Churchill then rallied the people of Britain and led them brilliantly through the darkest early days of the war—and on, eventually, to victory. There is truth in that. But a closer examination muddies the picture. In fact, viewing the events of those early days with a microscope, it’s hard to avoid concluding that the impression many share is highly misleading. In Darkest Hour, Anthony McCarten follows the men in the leadership of the British government day by day and at times hour by hour during the fateful month of May 1940. The result is a picture that is both more equivocal and more credible.

Most accounts of this time are oversimplified

McCarten’s account makes it clear that the conventional story of Churchill’s rise to 10 Downing Street is oversimplified in two ways. First, that he became Prime Minister only eight months after the Nazis invaded Poland, and only following bitter disputes at the top of the Conservative Party that came close to toppling the government of which he was a part. Second, and controversially, while Churchill consistently gave the impression to the public that he was willing to fight Germany to the last, in the privacy of War Cabinet debates he buckled at his weakest moment to demands from other Conservatives for a negotiated peace. And in this assertion, McCarten’s book parts company with almost every other history of that difficult time.

Darkest Hour: How Churchill Brought England Back from the Brink by Anthony McCarten (2017) 217 pages ★★★★★

A long history of misjudgment

If we are surprised that Neville Chamberlain managed to hang on as Prime Minister for eight months after the Nazi invasion of Poland, the explanation is simple. “Winston as supreme leader?” McCarten asks. “Winston Churchill in charge of everything? The 65-year-old word-spinner with a drinking problem and a decades-long history of misjudgement leading the country? Forget the country, you could forgive yourself for having reservations about lending such a man [a] bicycle.” That was, in fact, the prevailing view of Winston Churchill among his colleagues. The man had friends and supporters, but they were few by comparison with his detractors. That he attained the job he had coveted all his life came down to a single fact: there was no one else in the upper reaches of the British government with the credibility and the capacity to lead in wartime.

It was truly Britain’s darkest hour

Darkest Hour explores the time from Churchill’s election as Prime Minister on May 10 to June 4, 1940, when the last British troops left Dunkirk. While the tumultuous debates surrounding these events unfolded in Whitehall and on the coast of France, Hitler’s armies were crushing resistance throughout the Low Countries, northeastern France, Denmark, and Norway. His generals began preparations to invade Britain, which the men at the helm in London expected to occur within weeks. It was, indeed, Britain’s darkest hour.

A five-man War Cabinet

Shortly after forming his government, Churchill appointed a War Cabinet that consisted of five men representing the two major political parties. Two were Conservatives like him—Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940) and Viscount Halifax (1881-1959)—and two represented the Labour Party, Clement Attlee (1883-1967) and Arthur Greenwood (1880-1954). Both Chamberlain and Halifax were bitterly opposed to Churchill’s leadership and persisted for weeks after his appointment in their efforts to force a negotiated peace. To counter their influence, Churchill turned to Attlee and Greenwood. But Chamberlain and Halifax overshadowed them, and the majority in the Conservative Party favored them over Churchill.

Thus he played a weak hand until the successful evacuation of the British Army from Dunkirk silenced them. The Prime Minister later expanded the War Cabinet to eight members once Chamberlain died and he was able to drop Halifax by appointing him Ambassador to the United States. He thus became free of his two most hostile opponents.

The most dramatic revelation

The more detailed histories of that troubled month make clear that Churchill’s path to 10 Downing Street was rocky, indeed. But few if any of them delve so deeply into the early War Cabinet debates as does McCarten’s. By turning to contemporaneous accounts slighted or ignored by other authors, he finds persuasive evidence that Halifax and Chamberlain forced him to accede to sending peace feelers to Italy. The move, initiated by Halifax, was intended as the opening move in a plan to achieve a general European peace. McCarten makes clear that the plan was naive at best and would doubtless have failed. But he cites several reports in the diaries of men who were in the room that Churchill did for a time agree to allow Halifax to proceed.

“[A] close reading of the minutes,” McCarten writes, “reveals not only a leader in trouble, under attack from all sides and uncertain what direction to take. . . How close did Winston come to entering into a peace deal with Hitler? Dangerously so, I discovered.” The author notes that “Chamberlain’s diary . . . records him saying ‘it was incredible that Hitler would consent to any terms that we could accept—though if we could get out of this jam, by giving up Malta & Gibraltar & some African colonies, he [Winston] would jump at it.'” And other accounts by participants confirm this. Churchill was on the brink of despair. McCarten rejects assertions by some authors that the Prime Minister’s move was manipulative, knowing that Hitler would never agree to any terms acceptable in London. The evidence he cites is persuasive.

Churchill’s oratorical brilliance

Churchill’s now legendary oratory is the central theme of Darkest Hour. “[W]hen Britain stood alone before a monstrous enemy, he mobilized the English language and sent it into battle. This isn’t merely a pretty metaphor. Words were really all he had in those long days.” Other accounts of the time include phrases and short passages (“we shall fight on the beaches,” “blood, toil, tears, and sweat”) from the Prime Minister’s speeches to the Cabinet, Parliament, and the British public. But McCarten proves his case with much lengthier excerpts. The effect dramatizes Churchill’s genius with the language.

About the author

New Zealand novelist, playwright, journalist, television writer and filmmaker Anthony McCarten was twice nominated for the Academy Award for Best Adopted Screenplay. He is the author of ten film screenplays, seven novels, and a nonfiction book, The Pope: Francis, Benedict, and the Decision That Shook the World, in addition to Darkest Hour.

For related reading

See The Duel: The Eighty-Day Struggle Between Churchill and Hitler by John Lukacs (When Churchill faced Hitler alone) for another account of Churchill during this critical period. And for a superb account of the Prime Minister later in 1940, see The Splendid and the Vile: A Saga of Churchill, Family, and Defiance During the Blitz by Erik Larson (An intimate view of Winston Churchill in WWII).

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 15 good books about the Holocaust

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- 10 great biographies

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.