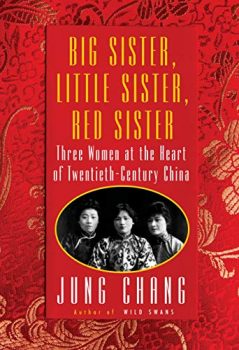

The three sisters’s lives spanned three centuries of Chinese history. Born late in the nineteenth century, the youngest of them died at the age of 105 in 2003. Together, these three extraordinary women helped shape the destiny of the world’s most populous nation from the closing days of the Manchu dynasty to the dawn of China’s ascension into a superpower. In Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister, the acclaimed Chinese-British historian Jung Chang tells their story with compassion and an obsessive attention to historical fact. In the process, she illuminates the story of twentieth-century Chinese history from a new perspective.

Three sisters who were at the forefront of twentieth-century Chinese history

In outline, the basic facts are these:

- The three sisters’s father, Soong Charlie, grew up poor but gained the advantage of a missionary education. Trained as a missionary himself in the United States, he found ways for all six of his children to gain American college degrees. They all became fluent English speakers.

Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister: Three Women at the Heart of Twentieth-Century China by Jung Chang (2019) 375 pages @@@@@ (5 out of 5)

- Soong May-ling (Little Sister) was the youngest of the three girls. (Their three brothers were all younger.) Having lived in the US from age nine to nineteen, she spoke English but was illiterate in Chinese, which she had to learn later in life. She married Chiang Kai-shek, the Soviet-backed soldier who became Generalissimo and later president of the Nationalist forces that dominated China until 1949. He then led the exodus to Taiwan, where he ruled until his death in 1975.

- Soong Ching-ling (Red Sister), married Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who has been credited as the “Father of China” for having played a leading role in the movement to overthrow the Manchu Dynasty. After his death in 1925, she sided against her family with the Communists. During the last three decades of her life she held an honored role in Red China as Vice-Chairman under Mao Ze-dong and Deng Tsiao-peng.

- Soong Ei-ling (Big Sister), the eldest of the children, was “the first Chinese woman to be educated in the United States.” She married an American-educated Christian banker named H. H. Kung. She guided him to an enormous fortune, much of it gained during the war with Japan when Kung served as finance minister and sometime prime minister in the Nationalist government. In fact, it was Ei-ling who was her brother-in-law Chiang Kai-shek’s most influential advisor, even though much of her advice had to be funneled through her husband or a younger brother who also served in Chiang’s cabinet.

- Ei-ling supported others in the family for many years through the fortune she and Kung had amassed, largely through commissions and kickbacks on weapons and other supplies from the US. “Eventually, the wealth amassed by the Kungs,” Chang reports, “may have reached, or even surpassed, $100 million” (the equivalent of at least $1.4 billion in 2019 dollars). And the corruption was anything but hidden. As President Harry S Truman famously said of the Soong and Kung families, “They’re all thieves, every damn one of them.” However, you can’t understand twentieth-century Chinese history without knowing about the role of this remarkable family.

Updating an earlier biography of the three Soong sisters

More than thirty years ago, I read an earlier biography of the three sisters: The Soong Dynasty by Sterling Seagrave, a bestseller published in 1985. That book, which “portrayed the Soong family in a highly unfavourable light,” shaped my views of some of the major figures in twentieth-century Chinese history, including Dowager Empress Cixi, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao Zedong, as well as the three Soong sisters themselves. Jung Chang’s treatment, benefiting from several decades of additional documents that have come to light, conveys a somewhat different picture. The Dowager Empress emerges in Jung Chang’s book as a committed and effective reformer, not the greedy and self-indulgent figure portrayed in the Communists’s rewriting of history. Both Sun Yat-sen and Chiang Kai-shek come across as scheming and amoral, the one incompetent at politics, the other disastrous as a military leader. And the three sisters, in Chang’s telling, are all fallible but believable human beings.

Because of decades of propaganda on all sides, the three sisters came to be regarded as what Chang refers to as “fairy-tale figures.” She cites the “much-quoted description: ‘In China, there were three sisters. One loved money, one loved power, and one loved her country.'” The reference to Big Sister, Little Sister, and Red Sister (in the same order) is, of course, a gross oversimplification. They and their lives were anything but simple.

Refuting the myths spread by propaganda

Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister upends a great many myths that have been propagated both by the Chinese government in Beijing and the China Lobby in the US.

Dowager Empress Cixi

The subject of an earlier biography by Jung Chang, the Dowager Empress was in reality a far worthier person than she is generally portrayed as being. “A former imperial concubine, this extraordinary woman had seized power through a palace coup after her husband’s death in 1861, whereupon she had begun to bring the medieval country into the modern age.” After earlier efforts at reform that are generally credited to the men in her court, she doubled down on the effort after the turn of the century. “In the first decade of the twentieth century,” Chang writes, “she introduced a series of fundamental changes. These included a brand-new educational system, a free press, and women’s emancipation, beginning not least with an edict against foot-binding in 1902. The country was to become a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament.”

Sun Yat-sen

Although Sun Yat-sen is typically referred to as the first president of China, in fact he was only acting president, and for a very short time. For more than a decade he struggled with opponents within the Nationalist Party (which he did not found) to gain the presidency. Allied with gangsters, Sun employed hardball tactics, including assassination, to gain power but was never successful. He was a womanizer and treated all three of his wives (Ching-ling was the third) very badly. “A friend once asked him,” Chang writes, “what his favourite pursuits were; he replied without hesitation: ‘revolution’ followed by ‘women’.”

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek is one of the most controversial figures of the twentieth century, particularly in the United States, where he was lionized by the China Lobby advanced by TIME Magazine publisher Henry Luce. Although Chiang did in fact lead the resistance to Japan (1937-45) despite Beijing’s propaganda crediting Mao Ze-dong, senior American military officers assigned as his aides universally regarded him as an utterly incompetent soldier and blamed him for the loss to the Communists. And he was a violent man with a volcanic temper who frequently beat his first wife and concubines (Little Sister was effectively his fourth wife). Like Dr. Sun before him, he partnered with Shanghai’s notorious Green Gang; although Chiang was trained in the Soviet Union and controlled by Stalin for several years, he put the gangsters to work murdering Communists once he broke publicly with the Party in 1928. He was also himself a murderer who assassinated one of Sun Yat-sen’s opponents. (“He shot Tao dead in the bed at point-blank range.”)

Mao Ze-dong

Mao’s impulsive and brutal policies that led to the deaths of tens of millions of Chinese people are well documented and widely acknowledged. What is less well known are the facts surrounding the Long March and the Red Army’s performance in World War II. As Chang reveals, when Mao’s forces were holed up in the southeast, they were highly vulnerable. Chiang’s army might well have annihilated them when they drove them from the region. But Chiang was negotiating with Stalin at the time and dependent on Soviet arms; murdering the Reds might even have triggered a Soviet invasion. Thus, he was content to herd the Red Army into the arid far northwest where he might later bottle up and kill them.

Chang relates a strange story that explains how Chiang managed to lose to Mao even though his armies were battle-tested and much stronger than the guerrillas who made up the Red Army. Chiang’s son, Chiang Ching-kuo, had been imprisoned in the USSR on Stalin’s orders to maintain leverage over the Nationalist leader. To secure his release after a dozen years, Chiang agreed to a meeting with Zhou En-lai at which the two men cut a deal “which led to the two parties forming a ‘united front’ as equal partners when the war against Japan started, within months.” The Nationalist cause quickly went downhill after that.

About the author

Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister is Jung Chang’s fifth biographical treatment of twentieth-century Chinese history. Her earlier subjects included Dowager Empress Cixi, Mao Zedong, Madame Sun Yat-sen, and her own family. Born in China, she lives in London with her husband, Jon Halliday, her coauthor on two of those books.

For further reading

You’ll find this book on The 40 best books of the decade.

I’ve also recently reviewed an excellent revisionist history of China in World War II, Forgotten Ally: China’s World War II, 1937-1945 by Rana Mitter—A gripping history of China in World War II.

You might also be interested in:

- 12 insightful books about China reviewed on this site;

- 20 top nonfiction books about history plus more than 80 other good ones; and

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.