Consider the Pacific Ocean. It’s the largest expanse of territory on the planet, spanning 63.8 million square miles. That’s seventeen times the territory of the United States, and ten times that of Russia, by far the largest nation on Earth. Should we wonder, then, why fleets of Japanese and American warships spent so much time hunting in vain to locate the enemy? That failure, and other misjudgments and blunders in the Pacific War, loom large in Richard Freeman’s illuminating account of the first six crucial months of 1942, Whirlwind: War in the Pacific.

Estimated reading time: 7 minutes

The six-month turnaround in US fortunes

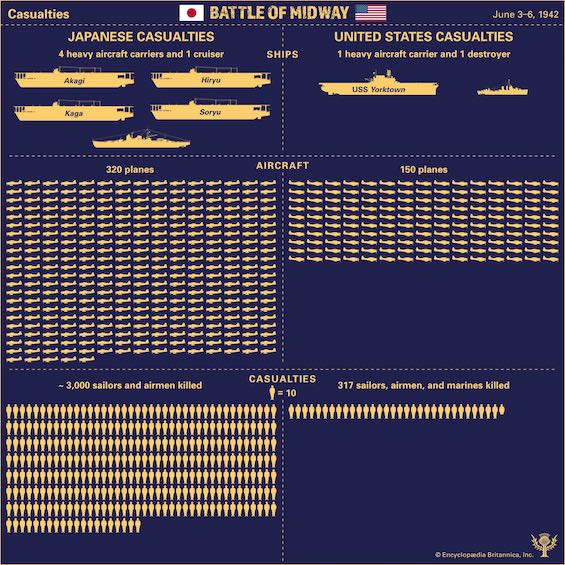

Within just six months of the devastating attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States Navy reversed the strategic trajectory of the war in the Pacific. By mid-June, the Japanese Imperial Navy was on the defensive. In the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 4-8, 1942), the American fleet met the best the Empire could bring to the war and fought them to a standstill. And at Midway (June 4-7, 1942), US forces under Admirals Jack Fletcher and Raymond Spruance cut the heart out of the Japanese Navy, destroying four of the empire’s six heavy aircraft carriers. Afterwards, despite Japanese gains on the Asian continent, the die was cast for the United States to prevail. And it’s those three battles—Pearl Harbor, the Coral Sea, and Midway—that Richard Freeman analyzes in Whirlwind.

Whirlwind: War in the Pacific by Richard Freeman (2018) 238 pages ★★★★☆

Blunders and misjudgments on both sides at Pearl Harbor

From the very first, faulty thinking set the course of the war in the Pacific. Had the commanding officers on both sides been thinking straight, the disaster at Pearl Harbor never would have happened. Believing that an attack on Hawaii was impossible, US commanders on the island utterly failed to take even the most modest steps to protect the fleet from attack. But the Japanese error was greater still. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who conceived the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, understood perfectly that the Japanese Empire could never win a protracted war against the United States. But he was convinced that by destroying the Pacific fleet, he could force the United States to sue for peace.

Yamamoto’s misconception reflected an ongoing pattern within the Japanese military, which consistently underestimated American resolve and fighting ability. And in execution, the Pearl Harbor gambit was a failure because Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who led the task force attacking the island, failed to order the destruction of the navy repair yards, oil tank farms, and submarine base. That failure, combined with the fact that the US fleet’s three aircraft carriers were hundreds of miles away, sealed Japan’s fate. The attack was considered a tactical victory but a strategic blunder. But in fact it failed even on a tactical level. As Freeman observes, “Pearl Harbour was a disaster for the Japanese, from which they never recovered.”

Errors throughout the war in the Pacific

Similarly, in planning that proceeded the Battle of Midway, the headquarters staff of the Imperial Japanese Navy overruled Yamamoto’s demand to deploy all six of their large aircraft carriers. They insisted on a separate, simultaneous attack on the Aleutian Islands with a smaller task force centered on two of the carriers. It’s clear in hindsight that, despite the brilliance Admiral Chester Nimitz displayed in setting the strategy for the Battle of Midway and the superb performance of Admirals Fletcher and Spruance there, Yamamoto would almost certainly have prevailed if he had had six rather than four aircraft carriers at his disposition.

In smaller ways, too, misjudgments and blunders influenced the course of events. Again and again, both Japanese and American pilots scouting or attacking enemy fleets mistook smaller ships for larger ones, confusing cruisers for flattops and destroyers for battleships. More to the point, they routinely reported much greater success in scoring hits on enemy ships than was the case. Many times, reports that they’d sunk or disabled ships turned out to be sheer fantasy. And such an error played a factor in the US victory at Midway. The Japanese were convinced they’d sunk two US carriers in the Battle of the Coral Sea, not one. As a result, they took chances they shouldn’t have taken—and paid the price when the US carrier they thought they’d sunk showed up just miles away.

Who was most responsible for the debacle at Pearl Harbor?

Most historians fault Admiral Husband Kimmel for failing to protect the US fleet at Pearl Harbor. He was in command of the Pacific Fleet based there. And, yes, there is some cause for blame. He ignored repeated warnings from Washington that war with Japan was imminent. But, as Freeman points out in Whirlwind, “the primary responsibility for protecting the island and the fleet was that of the army. It was the army that had the radar stations and the air bases from which most of the fighters and bombers would take off.” But the man in charge, Lieutenant General Walter Short, utterly failed to do his job.

Short refused to believe that an attack by Japan was possible, insisting instead that the real threat came from sabotage and subversion from Hawaii’s substantial Japanese and Japanese American population. He didn’t consider radar worthwhile and left the station in the hands of untrained rookies. He didn’t order air patrols around the islands. And he had the army’s planes parked wingtip to wingtip in tight formation on the tarmac, making them sitting targets.

Both Short and Kimmel were relieved of their commands after Pearl Harbor. Generals are rarely court-martialed, but Short would have been an obvious candidate.

Detailed, blow-by-blow accounts of the three signature battles

Freeman packs colorful detail into his story on almost every page. He names names, citing the experience of enlisted men and officers alike on board ships, in the air, and on land. Here, for example, is a representative passage of the action on the Coral Sea: “Lexington’s planes had launched shortly after Yorktown’s. Her attack group consisted of Ault with four scout bombers, Hamilton with 18 dive-bombers, and Brett with 12 torpedo bombers. The bombers were loaded with 1000 lb weapons and were accompanied by nine fighters led by Lieutenant Noel Gayle. Lexington turned into the 15 knot wind to aid their launching.” Such details lend authenticity to Freeman’s account and enliven the reading experience.

About the author

Richard Freeman‘s biographical blurb on Amazon reads as follows: “Richard Freeman writes books on naval history and the people who made that history. Amazon readers have greeted his style with phrases such as ‘Freeman makes military history interesting’ … ‘Freeman’s accounts are so engaging’ … ‘The excellent writing skills of Richard Freeman’ … ‘Freeman is a master of scene setting’. His books regularly receive praise for combining accurate research with a compelling narrative.”

For more reading

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- Books about World War II in the Pacific

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.