December 1941. The second of Herman Wouk’s two World War II novels opens. The entry of the United States into the conflict finds US Navy Captain Victor “Pug” Henry, his family, and friends scattered about the globe.

- Henry himself is now in command of the heavy cruiser Northampton, the consolation prize for the battleship he was supposed to lead, which is now heavily damaged at Pearl Harbor. The Northampton is the flagship of Admiral Raymond Spruance‘s fleet in the Pacific. It’s a choice posting.

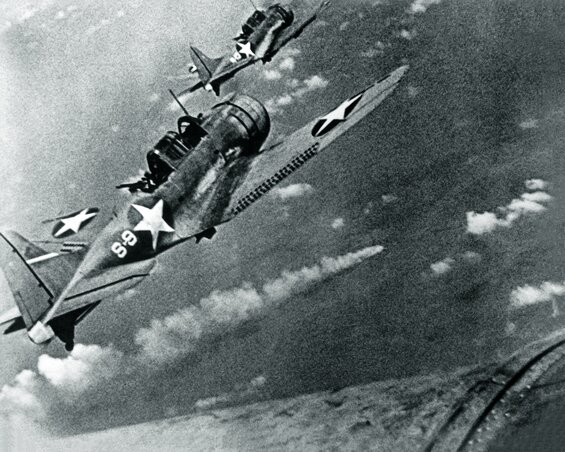

- Henry’s elder son, Warren, now a US Navy Lieutenant, pilots a dive-bomber housed on the carrier Enterprise under Admiral William “Bull” Halsey.

- Warren’s younger brother, Byron (“Briny”), is aboard the submarine Devilfish on a perilous mission to Lingayen Gulf, where the Japanese are landing the first of several divisions to seize the Philippines.

The “winds of war” have scattered the family across the Earth

Meanwhile, the three men’s wives are dispersed even more widely. Rhoda, Pug’s wife, remains in their palatial home in suburban Washington, DC. There, she continues her on-again, off-again affair with Dr. Palmer Kirby, who is involved in the early stages of the US nuclear development program. (The Manhattan Project was launched only in 1942.) Warren’s wife, Janice, lives in the hills above Honolulu, above what is home base for her husband. And Natalie, Briny’s fiancée, remains marooned in Italy with her uncle, Dr. Aaron Jastrow, the famous author of A Jew’s Jesus. Despite months of efforts, they have been unable to return to the United States due to alleged visa complications.

At the same time, Pug’s love interest, Pamela Tudsbury, has landed with her father, Alistair Tudsbury, in Singapore. A famous on-air correspondent for the BBC, the old man is there to report on the defense of the island against an expected Japanese attack.

Thus begins the second of Herman Wouk’s two World War II novels, War and Remembrance. The book chronicles their lives throughout the four turbulent years that follow.

War and Remembrance (World War II #2 of 2) by Herman Wouk (1978) 1,396 pages ★★★★★

A sober assessment of the war

Wouk’s tale may be challenging for many readers, because it’s far more than the story of one family and the people they encounter as the Second World War unfolds. In two different ways, Wouk uses his talent for supple narrative prose to assess the conduct of the war from a much broader perspective—a view from 30,000 feet, if you will.

A German perspective

In the character of General Armin von Roon, one of Wouk’s fictional creations, he renders a German military perspective on the war. Writing as Vice Admiral Victor Henry three decades after World War II, Wouk includes “translated excerpts” from von Roon’s imaginary treatises, World Empire Lost and its sequel, World Holocaust. These excerpts are scattered throughout the text. As translator and editor, Admiral Henry includes his own editorial comments, taking von Roon to task for self-justifying inaccuracies and distortions. But it’s clear at this far remove from that time that much of what “von Roon” writes is perceptive, however painful. For example, although von Roon despises Franklin Roosevelt and subjects him to withering criticism (much of it deserved), his admiration for the leadership skills of the US President comes through loud and clear. The general waxes poetic over Hitler at first but writes about him more and more negatively as the book approaches its end. He comes off poorly in comparison with FDR.

The omniscient third person

In essay-like, narrative passages, Wouk renders his own account of the events that transpired from 1939 to 1945. His judgment is sober and solidly grounded on historical research. (Even after more than forty years of new research findings, I noticed very few errors.) War and Remembrance, and its prequel, The Winds of War, were together sixteen years in the making. His purpose in devoting so much of his career to the project is not clear in The Winds of War, which comes across as a gripping novel of war overlaid with the love story of Byron and Natalie. But Wouk’s intention emerges clearly in this sequel, for the continuing emphasis on the fate of the Jews under Nazi occupation is no accident. Clearly, the author’s project in this prodigious work was to memorialize the Holocaust. And he does so in a poignant and powerful manner. It’s hard to forget the stories he tells about the members of the Jastrow family. But don’t get the impression that War and Remembrance is all about the Holocaust. It is, in fact, a panoramic view of World War II. There’s enough coverage of the decisive battles—in the Pacific, in the Soviet Union, in North Africa, and on the Western Front—to satisfy anyone eager for an account of the fighting that determined the outcome of the war.

World War II through Jewish eyes

Wouk introduced Lieutenant Byron Henry’s fiancée, Natalie Jastrow, and her uncle Aaron in The Winds of War. As the sequel unfolds, we see Byron and Natalie marry and immediately separate again, divided by thousands of miles as he returns to submarine duty in the Pacific and she stays behind in Siena. Following Pearl Harbor, the two American Jews become interned in Italy. As conditions worsen, they escape to Vichy France, move to Paris and Baden-Baden under thinly-veiled Swiss protection, only to end up in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. Later, as the war hurtles toward its end, they are “transported” by the SS to concentration camps in the East.

Meanwhile, we also follow the odyssey of Berel Jastrow, Aaron’s cousin. Aaron and Berel had grown up as yeshiva students in a village in southwestern Poland near Oświęcims, the small settlement that came to be known to the outside world as Auschwitz. Aaron had dropped out of the yeshiva, rejected his family’s religiosity, emigrated to the United States, joined the Yale faculty, and written his Book-of-the-Month Club bestseller, A Jew’s Jesus. Unlike Aaron, who remains unfazed by the war during its early years, others in the Jastrow family fall under the German occupation. Only Berel escapes to join the Red Army. Later, a German POW, he escapes again, joining the partisans operating behind Nazi lines in the western reaches of the Soviet empire. Then he is captured yet again, ending up on a laboring crew building the Auschwitz and Auschwitz II-Birkenau death camps. Miraculously, he escapes Auschwitz and again joins a partisan band. Thus, we gain a Jewish perspective on the Final Solution from both fronts of the war, East and West.

Don’t think Wouk’s account of Berel Jastrow’s story is far-fetched. He based the tale on real-life accounts of numerous escapees from German camps, including several who fled the Nazis at Auschwitz with photographic evidence of the Final Solution, as does Berel.

Inside the US State Department

Earlier in life, Natalie Jastrow had lived in Paris, where she became acquainted with a brilliant American Rhodes Scholar named Leslie Slote. Now, years later, Slote has become a consular official for the United States. At successive postings in Berlin, Rome, Moscow, and Geneva, he too gains a front seat on the conduct of the war. And gradually, as he learns more about the Nazis’ “Final Solution,” he becomes progressively more frustrated and angry with the failure of the Allied governments to do anything about it. His reputation spreads through diplomatic circles, and eventually he receives first one, then several, bundles of documents, photos, and film clips that establish the horrific reality of the Holocaust. Historians have long since attributed the resistance of the US State Department to acting on any of this evidence to anti-Semitism. (Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long is usually identified as singularly responsible for blocking entry of Jewish refugees, and he appears in Wouk’s account.) Leslie Slote’s experience brings to life the experience of working in that environment.

About those famous names

Throughout the 2,300 pages of these two novels, you’ll find recognizable names from the history books. Wouk’s personal experience of the war—he served as an officer in the US Navy in the Pacific—and his extensive research allow him to render portraits of many of the leading figures of the day. My own reading makes clear to me that his portrayals are right on target. But the stories he tells permit him to do more than simply convey to readers an accurate sense of personality and patterns of speech. He’s also able to get across an impression of how these men’s actions—they were all men—stack up against their reputations. And two men come through loud and clear as undeserving of the heroic stature history has granted them: General Douglas MacArthur and Admiral William Halsey.

MacArthur and Halsey routinely appear high on the list of the leaders who won World War II. In reality, as the events in these novels make clear, both men should have been sacked for the egregious errors they committed. MacArthur unaccountably left aircraft stacked wingtip-to-wingtip on the tarmac at Clark Field, ignoring ample warning that the Japanese were about to attack the Philippines within hours. Most of the planes were destroyed or disabled. And Halsey nearly lost the Battle of Leyte Gulf by chasing after a decoy fleet of useless aircraft carriers sent far to the north by the Japanese and leaving the American landing force almost unprotected in the gulf. There were other reasons as well for removing the two men from their commands. But, in both cases, they were heroes to the media and the American public, and it was politically impossible for Roosevelt to remove them from the Pacific. (Apparently, he never considered doing so in the case of Halsey, but there was bad blood between FDR and the imperious MacArthur and the President may have been tempted in his case.)

A word about the Audible edition

I “read” both War and Remembrance and its prequel by listening to the Audible editions. All 101 hours of it. It took months. But the story held my attention throughout. The narrator, Kevin Pariseau, did a superb job. He’s a gifted mimic who managed to simulate both male and female voices, not just in English but in other languages from time to time. His pronunciation of German, French, Russian, and Italian was, for the most part, well done. (I know enough German to have caught him in a few errors, but not many, and have traveled enough to know the pronunciation rules for other major European languages.) There aren’t many stories that could hold my attention for so long. War and Remembrance is brilliant.

For more reading

Check out my review of The Winds of War (Is this classic World War II novel the best ever?). I’ve included a biographical sketch of the author in that review.

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 15 good books about the Holocaust, including both fiction and nonfiction

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

- Top 20 popular books for understanding American history

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.