Like a lot of Americans, I do my utmost to avoid talking, or even thinking, about death and dying. Maybe I’m just too close to the inevitable at 73 years of age as I write. Atul Gawande, the brilliant Indian-American physician and New Yorker writer, is clearly nowhere near my age, but in Being Mortal he’s made the topic palatable even for me.

Estimated reading time: 4 minutes

This book is a wake-up call to the healthcare industry to deal with dying not as something to be “fixed” with heroic, last-minute measures, whatever the patient might say, but as a natural process in which patients who wish for cessation of pain should be heeded above all. Being Mortal is a cry for compassion, a plea for doctors, nurses, and hospitals to integrate the compassionate contemporary version of hospice care into their services, allowing the terminally ill to die in peace at home.

Gawande makes his case through a series of vignettes that illustrate both the folly of the conventional wisdom of death and dying in the healthcare system and the beauty of the hospice approach that allows death with dignity. Again and again, he drives home the point that the traditional approach that is doctor-centric far too often leads to unnecessary and often unwanted suffering, whereas the patient-centric model of hospice care allows people to die in peace.

Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End by Atul Gawande ★★★★★

He surveys the history of nursing homes, the rise of assisted living, and the evolution of hospice care from in-patient to out-patient care. He emphasizes that the roots of the challenge lie in the loss of tightly knit families in contemporary societies and the profound increase in life expectancy over the centuries, from 28 in the heyday of the Roman Empire to near 80 or more today. “Old age and infirmity,” he writes, “have gone from being a shared, multigenerational responsibility to a more or less private state — something experienced largely alone or with the aid of doctors and institutions.”

This transformation is profound. “Whereas in early-twentieth-century America 60 percent of those over age sixty-five resided with a child, by the 1960s the proportion had dropped to 25 percent. By 1975 it was 15 percent. The pattern is a worldwide one.”

In the most personal passages in Being Mortal, Gawande writes about the death of his grandfather in traditional India, at home surrounded by three generations of his family, and that of his father in the United States, which was protracted and intensely painful because the old man (a doctor himself) for many months insisted on doing everything to give him more time — and, in the process, lost opportunities to enjoy life and accept death instead.

The nub of Gawande’s thesis

Here’s the nub of Gawande’s thesis: “This [pattern] is the consequence of a society that faces the final phase of the human life cycle by trying not to think about it. We end up with institutions that address any number of societal goals — from freeing up hospital beds to taking burdens off families’ hands to coping with poverty among the elderly — but never the goal that matters to the people who reside in them: how to make life worth living when we’re weak and frail and can’t fend for ourselves anymore.”

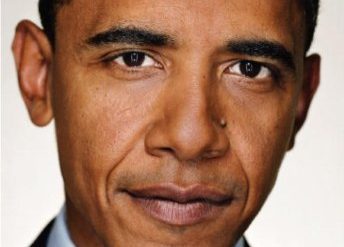

Atul Gawande is a general surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford and a MacArthur Fellow. Gawande first came to nationwide attention with a June 2009 New Yorker essay revealing the dramatically different costs of healthcare in two neighboring cities in Texas. His first bestseller was The Checklist Manifesto the following year.

For related reading

For a perspective on dying from a different angle, see Ageless: The New Science of Getting Older Without Getting Old by Andrew Steele (An aging reviewer tackles a book about aging).

You might also enjoy Science explained in 10 excellent popular books.

If you enjoy reading nonfiction in general, you might also enjoy:

- 10 great biographies

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- The 10 most memorable nonfiction books of the decade.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.