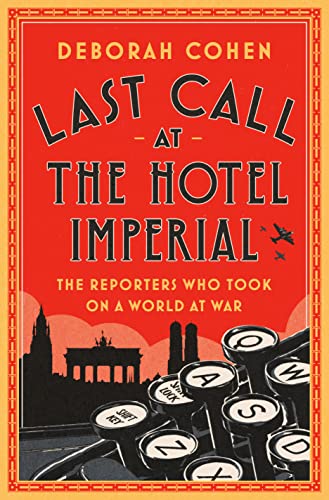

They were the media superstars of their time. Millions read their dispatches from overseas, listened to them on the radio, and attended their lectures. In today’s atomized media environment, there is no one who compares to the breadth of their influence on public affairs. The closest analogue were the network TV anchors of the 1960s and 70s. Walter Cronkite. Chet Huntley and David Brinkley. Peter Jennings. Celebrities, one and all. And historian Deborah Cohen brings them back to life in Last Call at the Hotel Imperial, her engaging group biography of the most celebrated American foreign correspondents of the 1930s and 40s. Without exception, they viewed war inevitable as the 1930s unfolded. And they helped lay the foundation for American intervention in Europe when at last it came to the USA.

Focusing on five men and women

Cohen chooses to center her account on what she calls the “inner circle” of American foreign correspondents. Three men and two women constituted a tightly-knit group who knew one another well (and sometimes slept with one another, or with their spouses). Only two of these five journalists linger in memory today: John Gunther (1901-70), who wrote bestselling books based on his travels, and Dorothy Thompson (1893-1961), whose syndicated newspaper column and radio broadcasts made her the most influential woman in America after Eleanor Roosevelt. But, in their time, all five were famous and their observations and opinions widely followed.

Last Call at the Hotel Imperial: The Reporters Who Took On a World at War by Deborah Cohen (2022) 609 pages ★★★★☆

The principal subjects

John Gunther

Anyone old enough to have been aware of the world in the 1950s is likely to remember John Gunther. Although he was the author of 25 nonfiction works and seven novels, he was best known to the public for the “Inside” series (Inside Europe, Inside Asia, Inside U.S.A., and three later volumes about Africa, Russia, and South America). The books were runaway bestsellers, routinely featured by the Book-of-the-Month Club. Gunther interviewed national leaders, policymakers, cultural icons, and humble folk alike, conveying what he learned from them with often idiosyncratic comments of his own.

Frances Fineman

Frances Fineman was married to John Gunther from 1927 to 1944, although the couple frequently separated. Both were miserable for extended periods, as Cohen tells the tale. Fineman was a brilliant journalist in her own right, winning plaudits for her work when she managed to write up her stories. But she spent much of her energy, especially In the early years of their marriage, feeding ideas to Gunther. Sometimes he credited her in print, sometimes not. Together, the couple had a son, Johnny, who died at 17 of a brain tumor in 1947. Gunther’s memoir of Johnny’s death was among the first books to explore the theme. Death Be Not Proud was considered his finest work.

H. R. Knickerbocker

Texas-born H. R. (Knick) Knickerbocker (1898-1949), the son of a preacher, studied psychiatry at Columbia University. He reported from Berlin from 1923 to 1933, but Hitler immediately expelled him upon coming to power. Others in the “inner circle” later achieved the same distinction. He was critical of Nazism but admired Mussolini and the fascist state he was building in Italy. Knickerbocker won the Pulitzer Prize for a series of articles about Stalin’s first Five Year Plan. Later, he covered the Spanish Civil War. His wife, Agnes, carried on a years-long affair with John Gunther and led to the two men, previously the best of friends, becoming estranged.

Vincent Sheean

James Vincent (Jimmy) Sheean (1899-1975) wrote a dozen books but was best known for Personal History, a memoir of his experiences as a reporter overseas. The book won one of the first National Book Awards and became the basis of the film Foreign Correspondent, directed by Alfred Hitchcock in 1940. Sheean gained recognition for his reporting from the Spanish Civil War for the New York Herald Tribune. In 1963, in Dorothy and Red, he exposed the tumultuous marriage of his friends Dorothy Thompson and Sinclair Lewis, who was known as Red. Both were dead by then. Had they been alive, they would not have been pleased.

Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Thompson (1893-1961) was the most remarkable figure of the group and, by all accounts, the most famous in her heyday. She was one of very few women reporters on the radio in the 1930s and gained such prominence that FDR frequently consulted her. Her best-known work as a reporter were her dispatches from Germany. She met and interviewed Hitler in 1931 and wrote a book about it. Hitler expelled her from the country in 1934. In 1936, Thompson began writing a syndicated column, “On the Record,” for the New York Herald Tribune. The column was read by ten million people and gained her such a large following that NBC offered her a network radio program. She also wrote a monthly column for the Ladies’ Home Journal for 24 years.

Cohen relates a revealing story about Thompson and her husband. Dorothy and Red are lying in bed in the morning when FDR calls. The phone is on Red’s side of the bed, so when he hands her the phone, the cord stretches tightly across his neck, pinning him to his pillow. Dorothy and the President speak for half an hour. Red, of course, was Sinclair Lewis (1885-1951), who had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1930.

A flawed account

Cohen does an admirable job setting the scene in which these men and women plied their trade. Her account of their work in the 1930s is rich in detail and illuminating. But the book’s subtitle is misleading. Last Call at the Hotel Imperial isn’t really the story of The Reporters Who Took On a World at War. There is little about their work during the pivotal years of World War II (1937-45). And, throughout, Cohen devotes rather more attention to the on-again, off-again marriages of her subjects and their sex lives than she does to their interaction with the movers and shakers of the time. It’s almost as though, arriving at a stopping point late in the 1930s, she decided to cut the book short. Of course, that may have been her intention all along but the publisher insisted on imposing a misleading subtitle to increase the book’s appeal.

Please note that other American journalists were equally influential during the same period but are not central to Cohen’s story. Edward R. Murrow and H. V. Kaltenborn were radio journalists, not writers, and fall outside the parameters of Cohen’s book. And Walter Duranty of the New York Times may have been a Soviet agent. His disgraceful reports whitewashing Stalin’s genocide in the Ukraine were notorious—but he was widely regarded at the time at America’s leading expert on the Soviet Union. There were many other Americans reporting for newspapers from overseas in the 1930s and 40s—not to mention a much larger number of Europeans and others. But none of the others achieved equal impact.

About the author

Deborah Cohen (1968-) is a Professor of History at Northwestern University and the author of four books. She graduated summa cum laude from Radcliffe College in 1990, and completed her Ph.D. in history at the University of California, Berkeley in 1996. She is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Cohen is of Ukrainian Jewish descent. She grew up in Louisville, Kentucky.

For more reading

You might also enjoy:

- 10 top nonfiction books about World War II

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- The 10 best novels about World War II

- 13 great war novels reviewed here

- 7 common misconceptions about World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.