In March 1945, Allied commanders were shocked to discover that a small group of American soldiers had defied orders and engineered a strategic breakthrough that would shorten World War II. This remarkable little book is their story.

The strategic breakthrough: the context

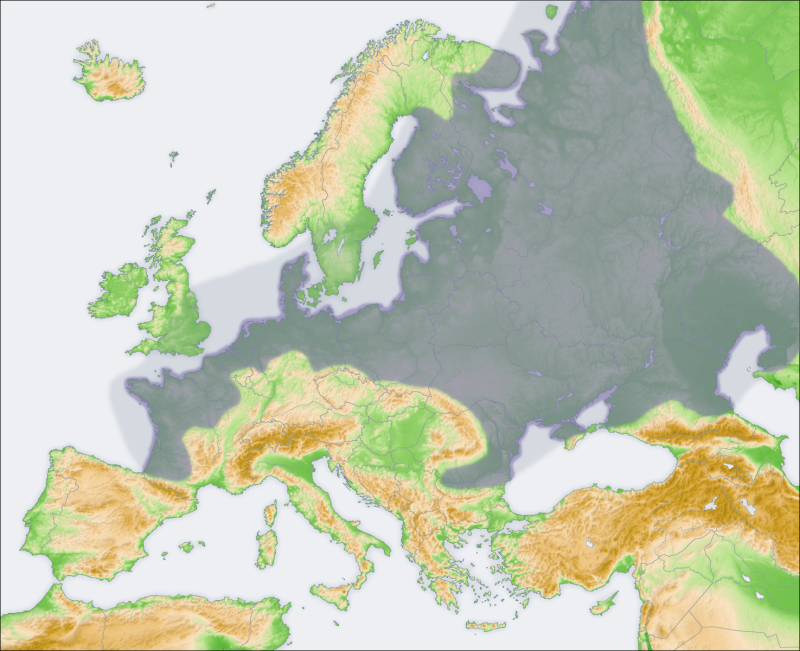

A vast, largely level plain sprawls westward from Moscow to Paris and beyond. Few formidable obstacles stand in the way of mobile modern armies that traverse this land in either direction. Over the centuries, however, the Rhine River in western Germany has stubbornly halted invading forces from the west, at least temporarily. That was the case for both Caesar and Napoleon. But in World War II, Allied plans to build overwhelming force before attempting to cross the river went magically awry. Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery was supposed to make the first crossing far to the north. But, to their commanders’ surprise, a small American Army had walked across the sole remaining intact span: the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen. Suddenly, the Allies had a clear shot at Berlin, 300 miles to the east. As Eisenhower himself later wrote, “The final defeat of the enemy, which we had long calculated would be accomplished in the spring and summer campaign of 1945, was suddenly, now, just around the corner.”

The Bridge at Remagen by Ken Hechler (1957) 282 pages @@@@ (4 out of 5)

The strategic breakthrough: the historical setting

By March 1945, Nazi Germany was all but beaten. In the east, Russian armies were rushing through Poland and approaching the outskirts of Berlin. In the west, Dwight Eisenhower‘s legions had overcome Nazi resistance in Normandy and were massing in western Germany and the Low Countries on their way to the Rhine. But German resistance was fierce, often fanatical, and the Rhine stood in the way. The Germans were under orders to blow every bridge when the Allies drew close. For Eisenhower and the generals commanding his armies in the field—Bernard Montgomery, Omar Bradley, George Patton, and others who today are less well known—were planning a massive pincer movement to encircle and destroy the remaining German forces west of the Rhine. Crossing the river and opening the way to Berlin would have to wait, or so they thought.

Then Second Lieutenant Karl H. Timmermann and a small detachment of his men unexpectedly came across an open, intact bridge across the Rhine. When, under heavy fire, they made their way more than 1,000 feet across to the eastern side, they opened a bridgehead that surprised both the Germans and their own superiors all the way up the chain of command to Eisenhower himself. In The Bridge at Remagen, military historian Ken Hechler tells their amazing story—one of the most remarkable episodes in all of World War II.

The ordinary men who engineered that strategic breakthrough

Hechler introduces Timmermann and his men and follows them through the bloody fighting that led them at length toward the town of Remagen. They were ordinary men, undistinguished in civilian life, with names that reflect the diverse history of the United States: Drabik, DeLisio, Mott, Dorland, Reynolds, Soumas, Miller, Goodson, Grimball, Chinchar, Petrencsik, Samele. Timmermann and these dozen men under his command were all awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and a long list of individual fighting units involved in the followup operation received Presidential Unit Citations. Thirty-two other soldiers died and sixty-three were wounded when, after the Allies made heavy use of the bridge for days, the structure collapsed into the frigid waters of the Rhine.

Five German officers were sentenced to death

Meanwhile, Hechler details the experiences of the German troops sent to defend—and, ultimately, to blow up—the Ludendorff Bridge. Through interviews in the early 1950s with many of the surviving German soldiers who had been posted to Remagen, he gained valuable insight into their perspective on the event. And he learned the grisly details of Adolf Hitler’s reaction to the shock of the Allies’ crossing the Rhine: upon the Führer‘s direct order, “five German officers were sentenced to death . . . for failing to blow the Remagen bridge.” And, as Hechler explains in detail, the fault lay not with these junior officers but with Hitler and the senior generals who commanded them. In the final analysis, the bridge remained intact because the Wehrmacht was losing the war. They were disorganized, desperately short of supplies, engaged in petty turf battles, and subjected to delusional orders from Berlin.

About the author

For nine terms, Ken Hechler (1914-2016) represented West Virginia in the U.S. House of Representatives. Later, he served for sixteen years as that state’s Secretary of State. However, as a young officer in World War II, Hechler was a member of a team of military historians. He was working in the vicinity when Timmermann and his men unexpectedly captured the Ludendorff Bridge. As he writes in the preface to this book, “Not long after receiving the electrifying news, I went down to Remagen and talked personally with some thirty officers and men directly involved in the crossing. . . I found [Timmermann] shaving in a bombed-out house east of the Rhine. His first reaction was to wonder what all the excitement was about.”

For further reading

For a military history of World War II on a larger scale, I recommend the work of Rick Atkinson:

- The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-44 (Friendly fire and bumbling generals in WWII)

- The Guns at Last Light: The War in Western Europe, 1944-1945 (“The greatest catastrophe in human history”)

You might also be interested in:

- 5 top nonfiction books about World War II (plus many runners-up)

- The 10 best novels about World War II (with 20+ runners-up)

- The 10 most consequential events of World War II

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, plus a guide to this whole site, on the Home Page.