For a century, from the 1870s to the 1960s, their family name was one of the most recognizable in the world. They were wealthy beyond the limits of imagination, and they married into European royalty and other ultra wealthy families such as the Rothschilds. Their roots lay in ancient Babylon. For the five hundred years from the fourteenth to the nineteenth centuries they were first among the Jewish families of Baghdad. Later, based in India and China, they built a fortune based on trading opium, cotton, and textiles. They dominated global trade in Asia for decades. Historian Joseph Sassoon tells their remarkable story with skill and colorful detail in The Sassoons.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

The author’s tenuous connection to the family

The author shares a surname with his subjects but is in fact only distantly related to them. He was born in Baghdad, while the Sassoons who flourished in commerce in Bombay, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and London had long since departed from Iraq. Their last common ancestor was the patriarch of the family in early 19th-century Baghdad, Sheikh Sassoon ben Saleh, father of David Sassoon, the merchant dynasty’s founder. As Joseph Sassoon notes in his introduction, “This book is thus intended to be not a family history but the history of a family.”

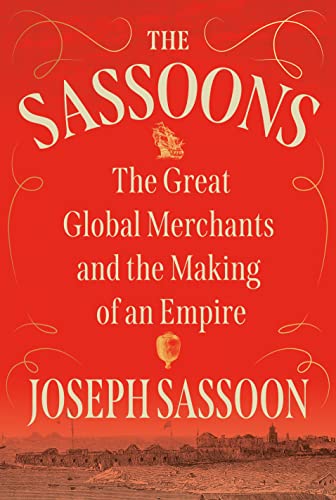

The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire by Joseph Sassoon (2022) 432 pages ★★★★☆

A fortune based on opium

The Sassoons is a story of four generations of the family. It might well be called “the rise and fall of the Sassoon empire.” The patriarch, David Sassoon (1792-1864), fled Baghdad in 1830 virtually penniless. He settled in Bombay and there established a trading firm. Success came slowly but steadily until by the 1850s the family had become one of the most prominent in India’s commercial capital. Their philanthropy was legendary. And the increasingly dominant role they played in trading opium yielded an immense fortune. As the author reminds us, “Opium became the world’s most valuable traded commodity in 1860 and remained so for a quarter of a century.” And it was legal everywhere except in China.

David Sassoon had eight sons and six daughters. When he died in 1864 control of the firm passed to his eldest son, Abdallah. But most of Abdallah’s seven brothers worked in the firm as well. While he remained at headquarters in Bombay, his brothers established offices in Hong Kong, Shanghai, London, and other, lesser cities. Their wealth and fame grew apace. Firmly allied with the British Empire, the family’s center of gravity steadily shifted to London.

In favor with royalty

Based in the imperial capital, the Sassoons gained favor with British royalty—two of the brothers befriended the Crown Prince and remained close both to him when he reigned as King Edward VII and his son, King George V. And along the way they gathered honors. Abdallah was the first, becoming Sir Albert Sassoon (1818-96), 1st Baronet. Others followed, as the younger generation increasingly shunned business and turned their attention to the pursuits of Britain’s upper crust. Theirs was the world of horse racing, gambling, palatial mansions, and marriages with Continental royalty. Over the years, the family’s fortune gradually shrank, divided among large numbers of sons and daughters and disappearing through their dissolute lifestyles. But business strategy played a role, too. Trading opium became progressively less profitable as the drug was increasingly restricted and later banned in most of the world. But they persisted in the trade long after it was profitable to do so.

Tensions between brothers led to a split

“Not quite three years after David’s death” in 1864, Joseph Sassoon writes, “simmering tensions between the two eldest brothers [Abdallah and Elias] culminated in a permanent split. From then on, two global businesses, both carrying the family name, would compete head to head.” Although competition spurred both firms to continue to innovate and grow, the distraction it caused became in the end a drag on their vitality. Sir Albert’s Bombay-based company continued to flourish for a time. But his brother Elias, based in Shanghai, gradually gained the advantage. And long after the original company had virtually disappeared, E. D. Sassoon & Co. continued to grow.

Under the direction of Sir Victor Sassoon (1881-1961), a member of the fourth generation, the firm ventured far from the family’s original business trading opium. E. D. Sassoon now invested heavily in Chinese real estate, building a fortune in excess of a billion dollars by the end of World War II. (One billion dollars then would be worth about $16 billion today.) But Sir Victor failed to anticipate the Communist victory and lost most of his fortune to nationalization after 1949.

The author’s unique research advantage

In commerce, the Sassoons had a unique competitive advantage: a built-in system of impenetrable code in the language they spoke. It was the Baghdadi Jewish dialect, sometimes now called Judeo-Arabic; it’s written in Hebrew characters. And the author, who shares that language with the family, thus was able to decipher the thousands of surviving letters among the family that have accumulated in historical archives over the years. The result is a detailed and ultimately fascinating picture of global commerce in the 19th century as well as the dynamics of a colorful and important family.

About the author

As his biography on the Georgetown University website notes, “Joseph Sassoon is Professor of History and Political Economy at Georgetown’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies and holds the al-Sabah Chair in Politics and Political Economy of the Arab World. He is also a Senior Associate Member at St Antony’s College, Oxford, where he also completed his PhD. Professor Sassoon, whose research focuses on political economy, economic history, Iraq, Iraqi refugees, and authoritarianism, has published extensively and is the author of five books.”

For more great reading

I’ve also recently read and reviewed The Last Kings of Shanghai: The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China by Jonathan Kaufman (The foreign businessmen who helped build modern China). The Sassoons were one of those two “rival Jewish dynasties.” And Kaufman’s account reveals a great deal about the family that doesn’t come to light in The Sassoons.

You’ll find books on related topics at:

- Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- Worthy books about Jewish topics

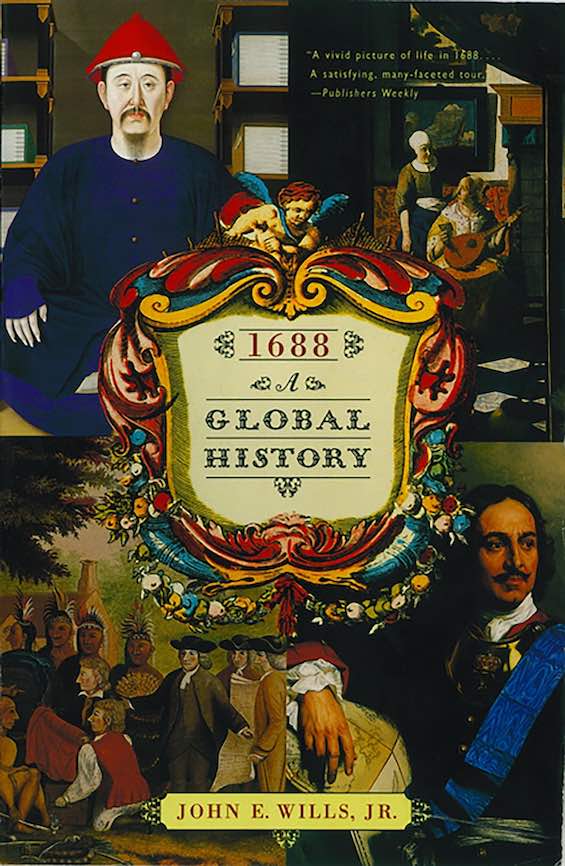

- 20 top nonfiction books about history

You might also care to visit 30 insightful books about China and Good books about India, past and present.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.