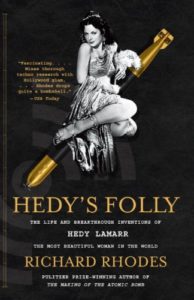

A quarter-century ago Richard Rhodes won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction for a masterful history, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, and he has received numerous plaudits in the years since, both for nonfiction and fiction. But I don’t see any prizes in his future for this half-hearted little effort, the story of Hedy Lamarr.

There’s nothing lacking in the material. It’s relatively well-known that Hedy Lamarr, a stunning film superstar of MGM’s Golden Age in the 1930s and 1940s, invented a secret weapon for the United States during World War II. However, the story—her extraordinary background, her flamboyant collaborator, and the the U.S. Navy’s ham-fisted response to their invention—was largely lost in obscurity and official secrecy until Richard Rhodes took it upon himself to write it up. I turned to the book with great anticipation—and was hugely disappointed.

The story is astonishing even in outline

A famously beautiful young Austrian woman named Hedwig Kiesler, daughter of a successful Viennese banker, found her incipient stage and film career interrupted when she married one of the richest men in Austria, a munitions manufacturer who happily participated in rearming Nazi Germany and supporting the most extreme of his country’s anti-Semitic Right-Wing politicians. (Hedy—she used the short form of her first name even then—was Jewish, though she hid that fact throughout her life, and her children learned about it only once she died.)

Hedy’s Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World, by Richard Rhodes (2011) 288 pages ★★★☆☆

Before she escaped from her first marriage, Hedy silently sat in on dinners and informal gatherings organized by her husband and attended by high-ranking Nazi generals and admirals. With an amazingly retentive memory, she fled with detailed knowledge of the Nazis’ most advanced weaponry—without her husband suspecting a thing, because to him she herself was just an object.

Soon after fleeing Vienna disguised as one of her maids in 1937, the year of the Anschluss with Germany, Hedy was recruited to MGM by Louis B. Mayer. Once in Hollywood, renamed Hedy Lamarr and dubbed “the most beautiful girl in the world” by Mayer (though others had previously tagged her with the phrase), she quickly became a major star. Although none of her films were especially memorable, they were successes at the box office and kept her in the limelight for many years.

Meanwhile, unbeknownst to nearly everyone who knew her in Hollywood, Hedy continued her life-long passion for inventing in her spare time. Once war had broken out in Europe, she devised a concept for a naval super-weapon—a torpedo guided by wireless radio, unlike the wired torpedoes then in widespread use. Together with her collaborator, George Antheil, an avante-garde composer whose concerts had sometimes caused riots in Paris and New York, Hedy offered the weapon to the U.S. government late in 1940.

A high school dropout but was clearly brilliant

Hedy had dropped out of high school to play a part on the Vienna stage, and she was neither a reader nor an intellectual of any stripe. However, she was clearly brilliant. The profound innovation she devised (with practical help from Antheil) was a system to make it impossible for enemies to jam the radio transmissions from the ship to the torpedo.

This innovation, first called frequency hopping and much later spread spectrum, “enabled the development of Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, the majority of cordless phones now sold in the US, and myriad other lesser-known niche products. The Global Positioning System (GPS) uses spread spectrum. So does the U.S. military’s $41 billion MILSATCOM satellite communications network. Wireless local area networks (wLANS) use spread spectrum, as do wireless cash registers, bar-code readers, restaurant menu pads, and home control systems.” Rhodes goes on for line after line, citing a plethora of additional applications of this seminal technology. In short, Hedy’s was one of those rarest of inventions that opened up vast new landscapes of possibility for engineers for many decades to come.

Her invention helped change the world

So, given the obvious appeal of the weapon she and Antheil had devised, one might think that the U.S. Navy, offered the patent in 1944 after seemingly endless vetting by a series of government scientists and engineers, would immediately put it into production. But no—the Navy classified the file top secret and stuck it in a filing cabinet. It was only discovered nearly 20 years later when an engineer working on a military contract chased down a rumor about Hedy’s invention, turned up the file, and began putting it to practical use.

A more nimble writer than Rhodes might have turned this story into a blockbuster. But sadly Rhodes devoted more space to the ups and downs of George Antheil’s career than to Hedy’s, and he goes on for page after tedious page about the mechanics of the wireless system, making the invention itself the principal character. Years ago, Tracy Kidder managed that beautifully in Soul of a New Machine. Perhaps as yet more information comes to light about this remarkable tale, Kidder or someone of comparable talent will do justice to one of the most remarkable women of the 20th Century.

For related reading

Like to read good biography? Check out Great biographies I’ve reviewed: my 10 favorites.

If you enjoy reading nonfiction in general, you might also enjoy:

- Science explained in 10 excellent popular books

- My 10 favorite books about business history

- Top 10 nonfiction books about politics

My post 10 top nonfiction books sbout World War II may also interest you.

And you can always find my most popular reviews, and the most recent ones, on the Home Page.